Election Blog

Week 1: U.S. Elections, Explained

Are you a first-time voter?

Or an international student trying to learn more about out U.S. Elections?

Perhaps you’re a political enthusiast curious about the intricacies of American democracy?

This blog is for you!

The once-every-four-year presidential elections in the United States of America attract attention from across the country and around the globe due to their potential impact on both domestic and foreign policies. Predicting the outcomes of these elections has, therefore, become increasingly important, given the U.S.’s position as a global superpower. However, before attempting to predict the outcome of the 2024 election, we should first understand how the election process works and, more importantly, gain a sense of how competitive U.S. presidential elections have been.

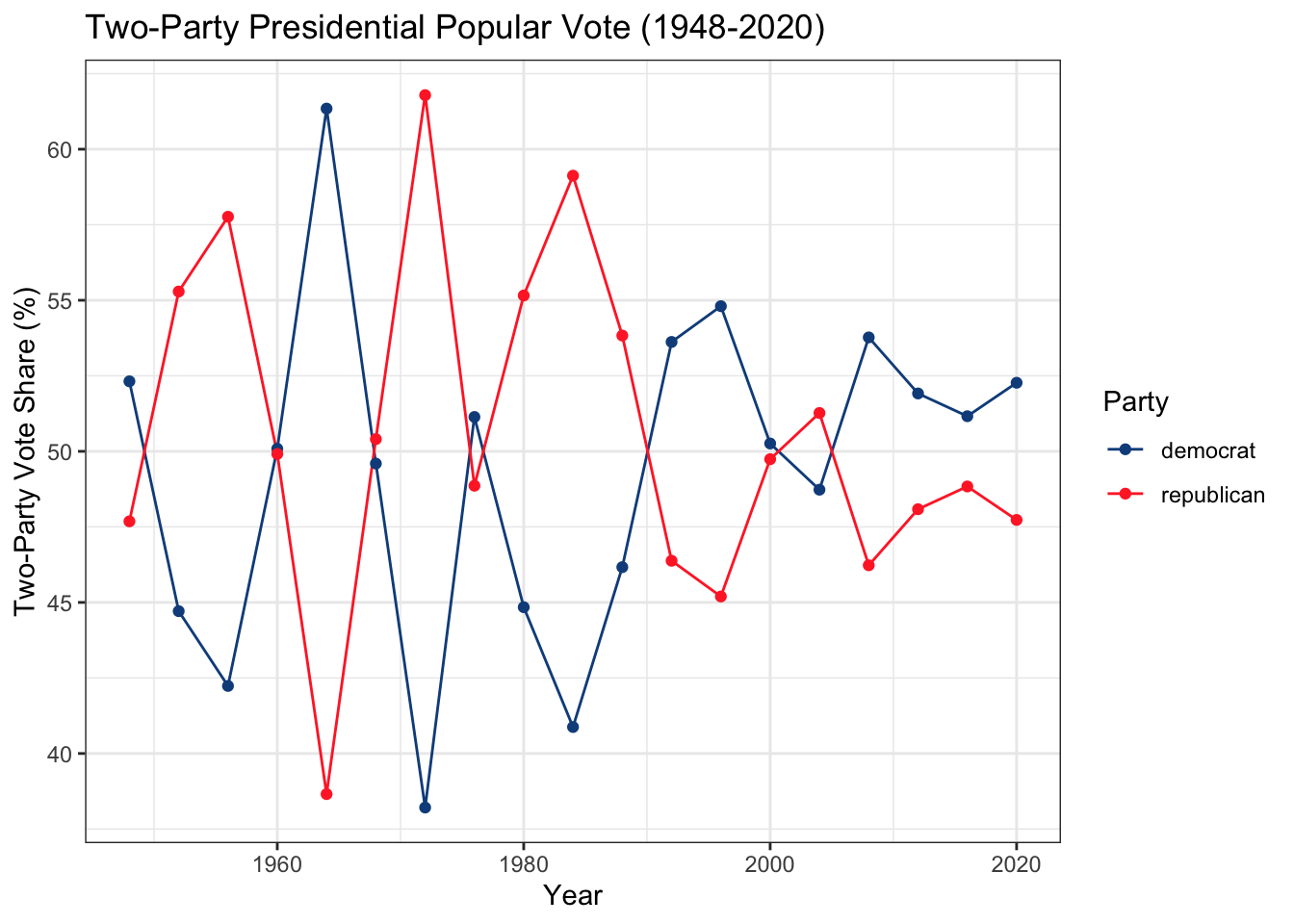

Over the past century, the two-party national popular vote share has seen significant fluctuations, particularly from 1964 to 1976, followed by a more competitive race in the years after 2000, illustrating the volatility of U.S. presidential elections. It is important to note that, for simplicity, this analysis excludes third-party candidates.

Who wins the presidency?

The winner of the U.S. presidency is determined by the Electoral College, not by the national popular vote. Imagine it’s November 5th, 2024, and you walk to your polling site, ready to cast your vote as a responsible citizen. Here, you are not directly voting for a presidential candidate. Instead, you are voting for electors pledged to vote for that candidate in the Electoral College. Each state has a specific number of electors, which varies based on the state’s population. For example, California, the most populous state, has 54 electoral votes, while smaller states like Wyoming have only 3.

To win the presidency, a candidate must receive a majority of the 538 total electoral votes — at least 270 votes. Most states (48 out of 50) use a “winner-takes-all” system, where the candidate who receives the most votes in that state wins all of its electoral votes. As a result, a candidate can win the Electoral College while losing the national popular vote.

Is the electoral college biased in determining who wins?

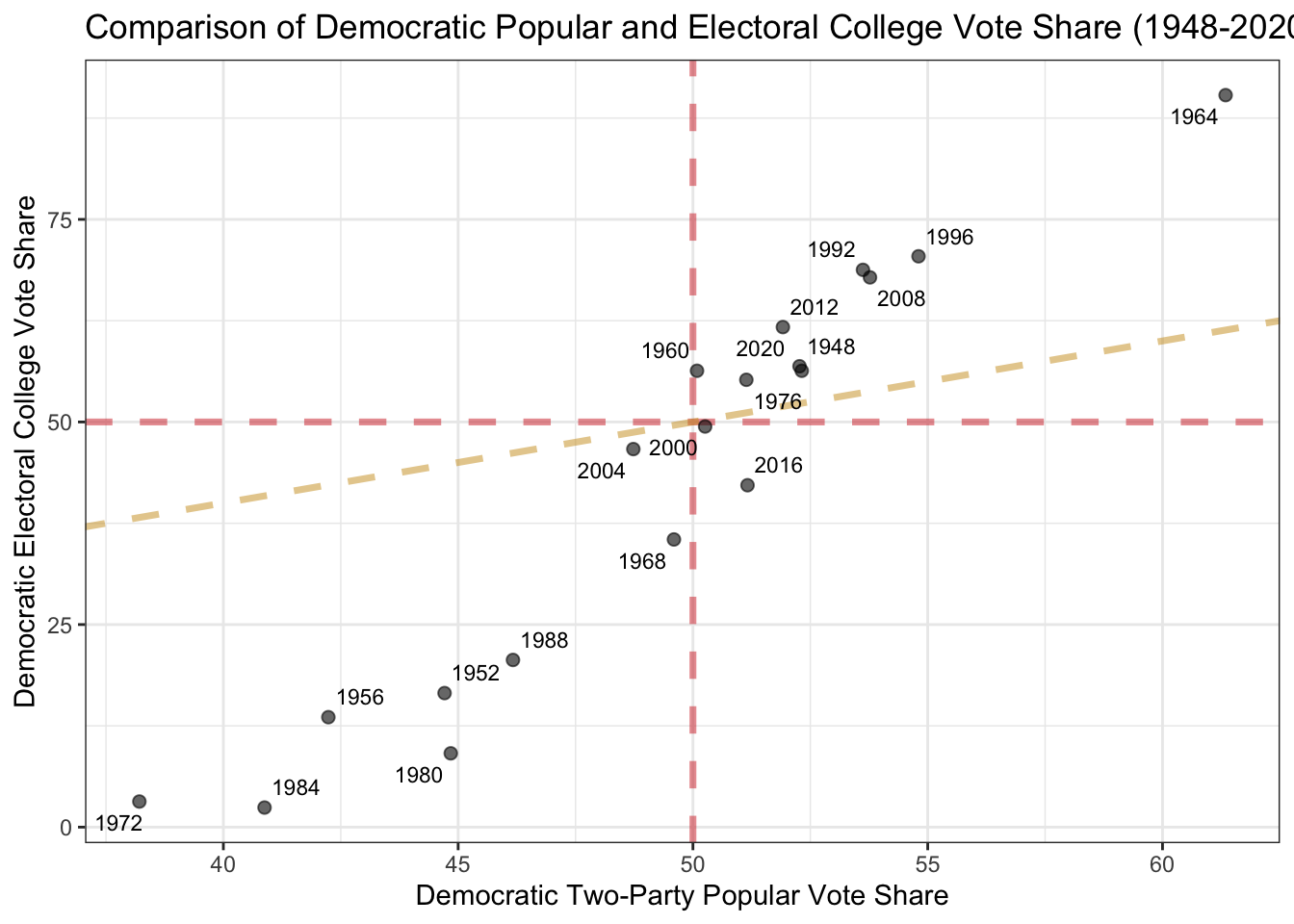

The graph above compares the share of the popular vote won by Democratic presidential candidates against their share of the Electoral College vote from 1948 to 2020.

The top right quadrant shows election years when Democrats won both the popular and the Electoral College votes. For example, in 1964, Democrats had a strong performance, securing a landslide victory in both. In contrast, the bottom left quadrant shows years when Democrats lost both the popular and Electoral College votes. Examples include the elections of 1984 and 1972, where Democratic candidates were decisively defeated, as indicated by low shares in both categories.

The bottom right quadrant represents scenarios where the Democratic candidate won the popular vote but failed to secure enough electoral votes to win the presidency. The 2016 election falls into this category when Donald Trump won the presidency despite losing the popular vote to Hillary Clinton by nearly 3 million votes.

There are no points in the top left quadrant, indicating that, since 1948, Democrats have never won the presidency through the Electoral College while losing the popular vote. Historically, it is rare for a candidate to win the Electoral College while losing the popular vote, though it has happened with Republican candidates (such as George W. Bush in 2000 and Donald Trump in 2016).

Trends in different states

The disparity between popular and electoral college vote share points to a potential bias in the Electoral College system, influencing candidates’ decisions on where to focus their campaigns. Since the outcome often hinges on a small number of battleground states, candidates invest heavily in these “battleground states” while overlooking states where the outcome is more predictable, potentially distorting national representation. This strategy is evident when examining historical election maps.

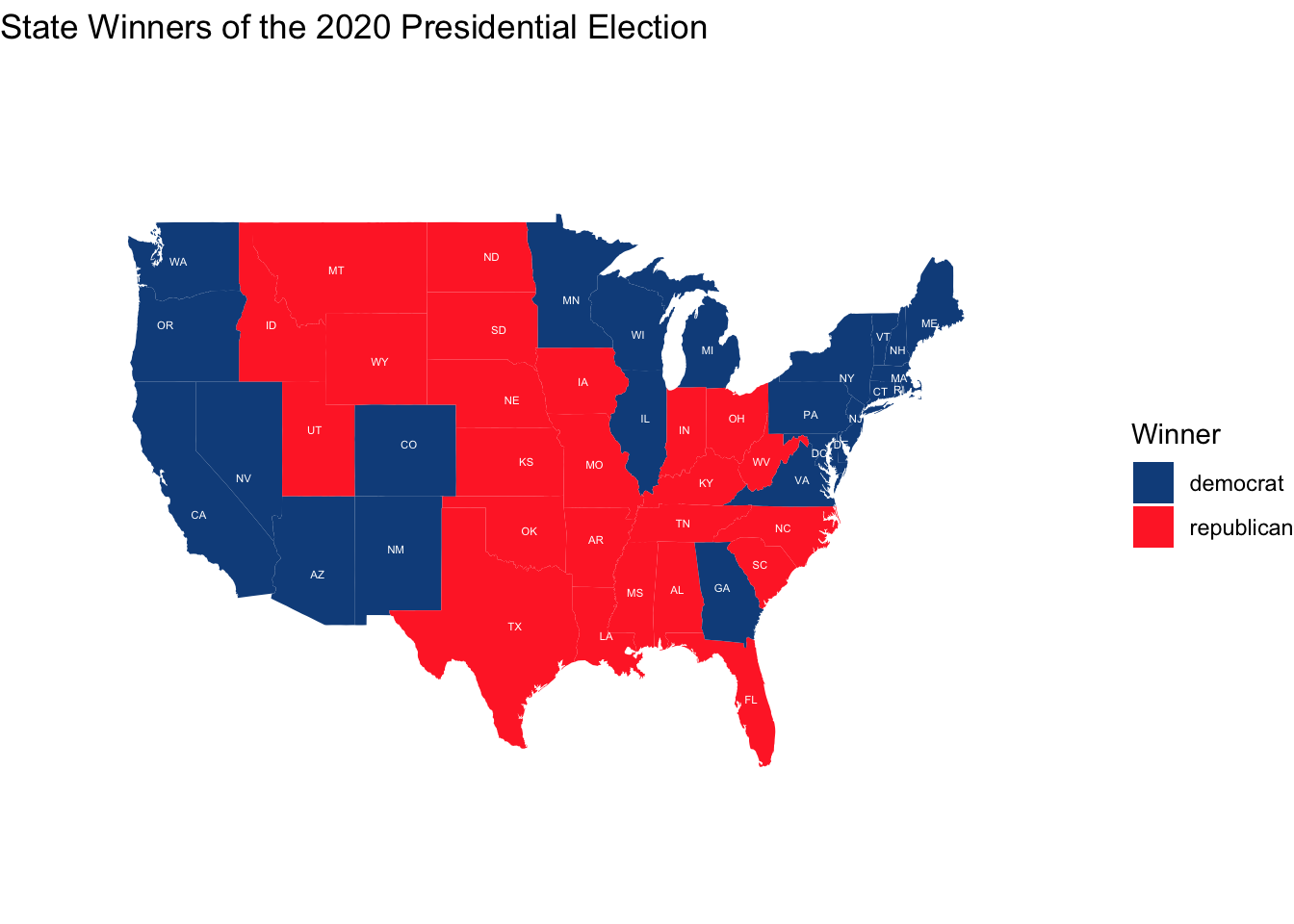

The map grid of state winners for the year 2020 above shows us which party each state voted for in the most recent presidential election, providing a snapshot of the current political landscape.

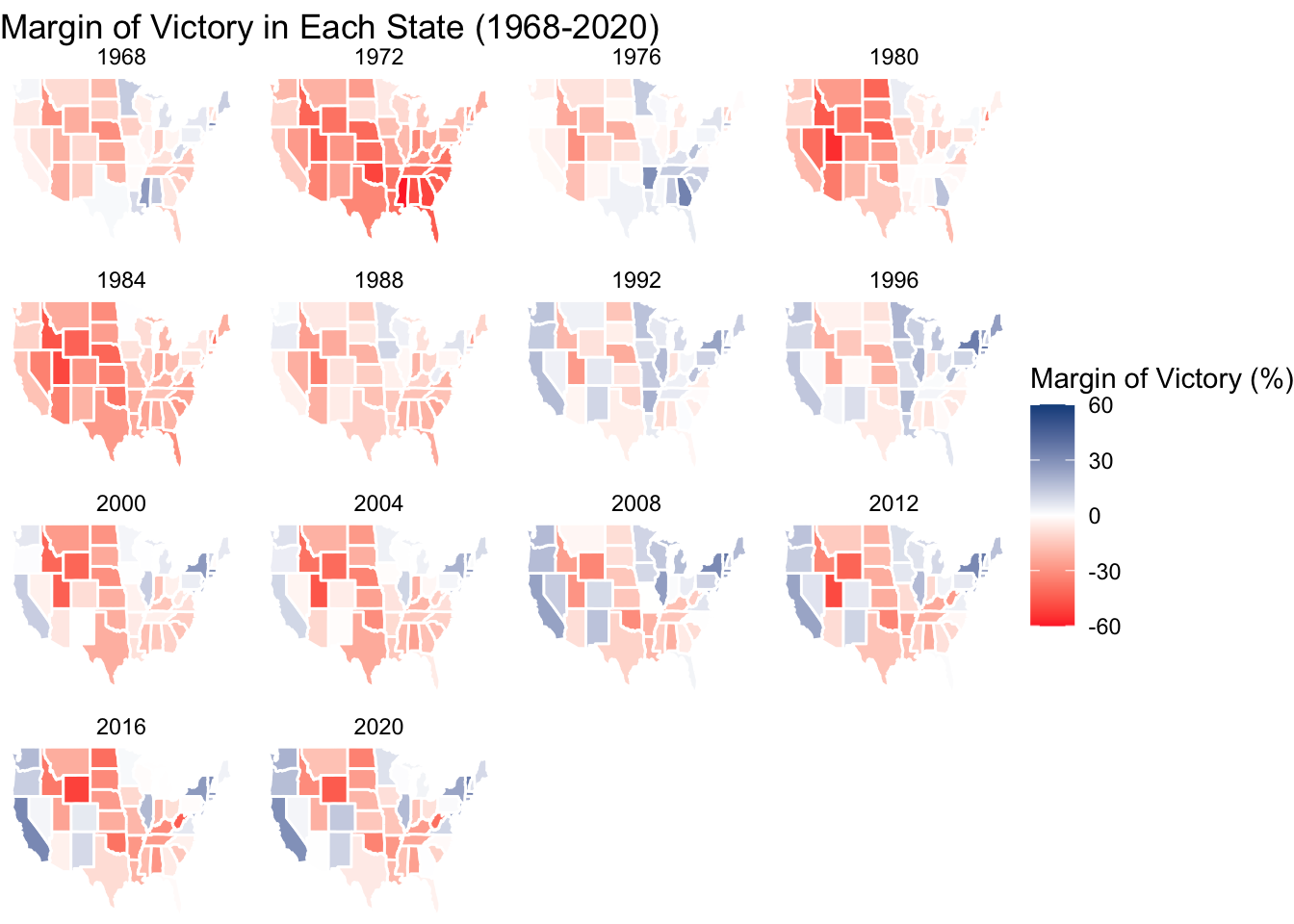

Using election data from 1968 to 2020 (to take into account changes after the Voting Rights Act and Civil Rights Act), the map series shows notable trends in the voting margins across U.S. states in presidential elections, reflecting shifts in political preferences and regional dynamics over time. This adds another layer of insight by showing not only which party won each state, but also the relative strength of their victory. By 2000, the map reflects a deeply divided nation, with clear red and blue state delineations that have become known as the modern “red state/blue state” divide. Democratic strength is concentrated in the Northeast, the West Coast, and parts of the Midwest, while Republican dominance is evident in the South, the Plains, and Mountain states. The margins in key battleground states like Florida, Ohio, and Pennsylvania become narrower, reflecting the highly competitive nature of U.S. presidential elections in recent years.

Sources:

- https://www.nytimes.com/article/the-electoral-college.html

- https://www.archives.gov/electoral-college/allocation

- https://www.statista.com/statistics/1077282/wining-political-party-us-presidential-elections/

Code developed with the assistance of ChatGPT.