Election Blog

Week 2: The Economy Matters

“Are you better off than you were four years ago? Is there more or less unemployment in the country?” Ronald Reagan asked these questions during his 1980 presidential campaign when he challenged the incumbent president, Jimmy Carter.

Indeed, general economic conditions, like GDP growth, inflation, and unemployment, can influence voters’ decisions in presidential elections. Achen and Bartels pointed out that ordinary citizens engage in retrospective voting, where they look at the past to judge how a politician might perform in the future, as a way of “rewarding” or “punishing” politicians. To illustrate an example, in 2016, Donald Trump’s slogan, “Make America great again,” prompted voters to think retrospectively to reflect on a past they believed to be better and urging them to vote for someone who could restore that sense of greatness.

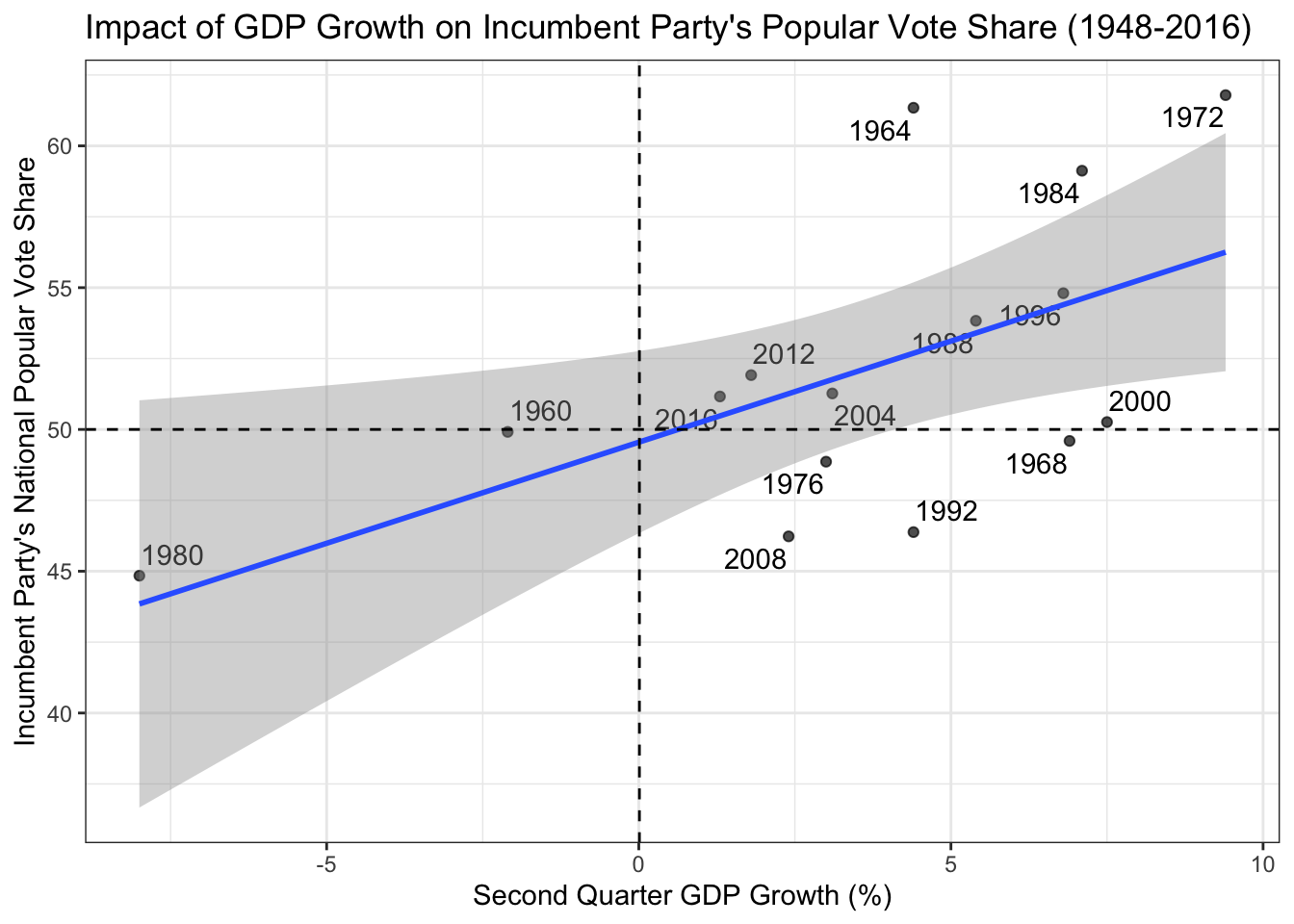

To see this dynamic in action, consider the regression results from an analysis of the second-quarter GDP growth during election years, using data from FRED and BEA. The table below shows the relationship between GDP growth and the incumbent party’s vote share:

| Term | Estimate | Std. Error | t-value | p-value | Lower CI | Upper CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| intercept | 51.395 | 1.213 | 42.356 | 0.000 | 48.793 | 53.998 |

| GDP_growth_quarterly | 0.265 | 0.138 | 1.921 | 0.075 | -0.031 | 0.561 |

What do the numbers tell us? If GDP growth in the second quarter of an election year is 0, the predicted two-party vote share for the incumbent party is 51.4%. A 1 percentage point increase in GDP growth corresponds to a 0.265 percentage point increase in the incumbent party’s vote share. While the relationship is positive, the relatively high p-value suggests that this effect isn’t particularly strong in this dataset.

However, if we exclude the 2020 election, an outlier due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the economic influence becomes more pronounced:

Now, the predicted vote share for the incumbent party with 0 GDP growth drops slightly to 49.6%, but the effect of GDP growth becomes stronger. A 1 percentage point increase in GDP growth results in a 0.713 percentage point rise in vote share, highlighting a more substantial link between economic performance and electoral success, supported by the small p-value.

| Term | Estimate | Std. Error | t-value | p-value | Lower CI | Upper CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| intercept | 49.550 | 1.488 | 33.310 | 0.00 | 46.336 | 52.764 |

| GDP_growth_quarterly | 0.713 | 0.270 | 2.638 | 0.02 | 0.129 | 1.297 |

The economy matters, but which economic indicators matter most?

Grocery prices are soaring, your job is boring, the markets are tanking. Among all these economic factors, which indicators best explain voters’ decisions to re-elect (or not to re-elect) the incumbent president or party? To answer this question, I used a regularized regression model. This method is useful when there are many potential predictors, like the various economic indicators we are examining, as it helps handle multicollinearity—when predictors are highly correlated with one another, which can make it hard to see the true effects of individual variables.

The plot above represents the coefficients of the regularized regression model, which shows how much each economic indicator contributes to predicting the incumbent party’s vote share.As seen in the plot, GDP growth in the second quarter of the election year has a positive coefficient. This suggests that when the economy is growing, it benefits the incumbent party, as voters may perceive economic growth as a sign of effective governance. Similarly, unemployment has a negative coefficient. Higher unemployment rates likely hurt the incumbent party’s chances of re-election, as voters might view rising unemployment as a result of poor economic management.

Variables like CPI (inflation) and real disposable income (RDPI) growth seem to have minimal effects based on the model’s coefficients. While the inflation rate and how much money actually enter one’s pocket is often used to gauge economic performance, it appears less predictive of voter behavior. Despite being commonly cited in media discussions of economic performance, the various S&P 500 stock market indicators (open, close, high, low, etc.) also have very small or zero coefficients. This suggests that the stock market might not play a significant role in voters’ decisions, or at least not enough to influence the election in a meaningful way.

Overall, voters seem to respond most strongly to how the broader economy is performing in terms of growth and job availability, rather than reacting to more volatile or less directly impactful factors like stock market fluctuations or inflation.

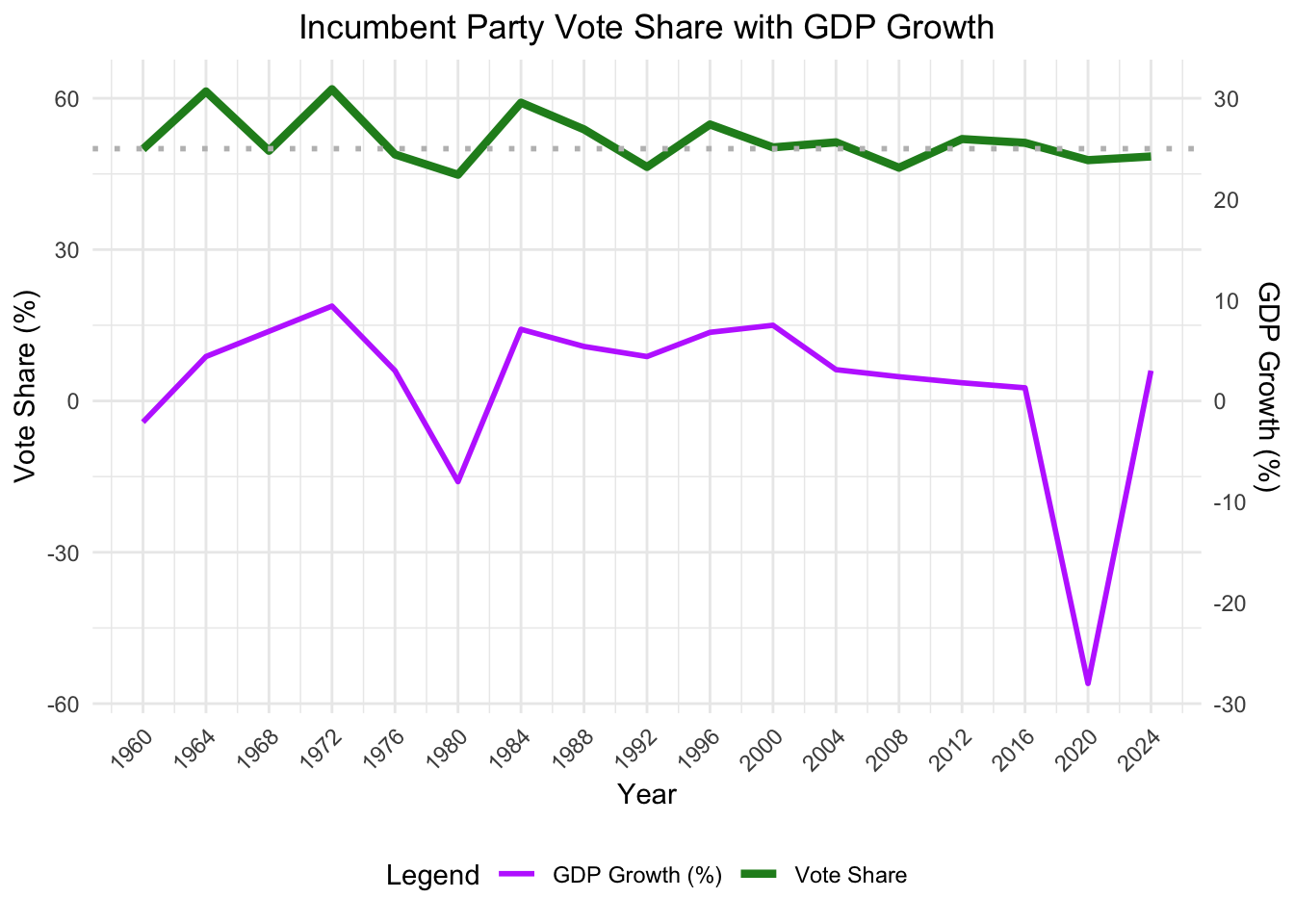

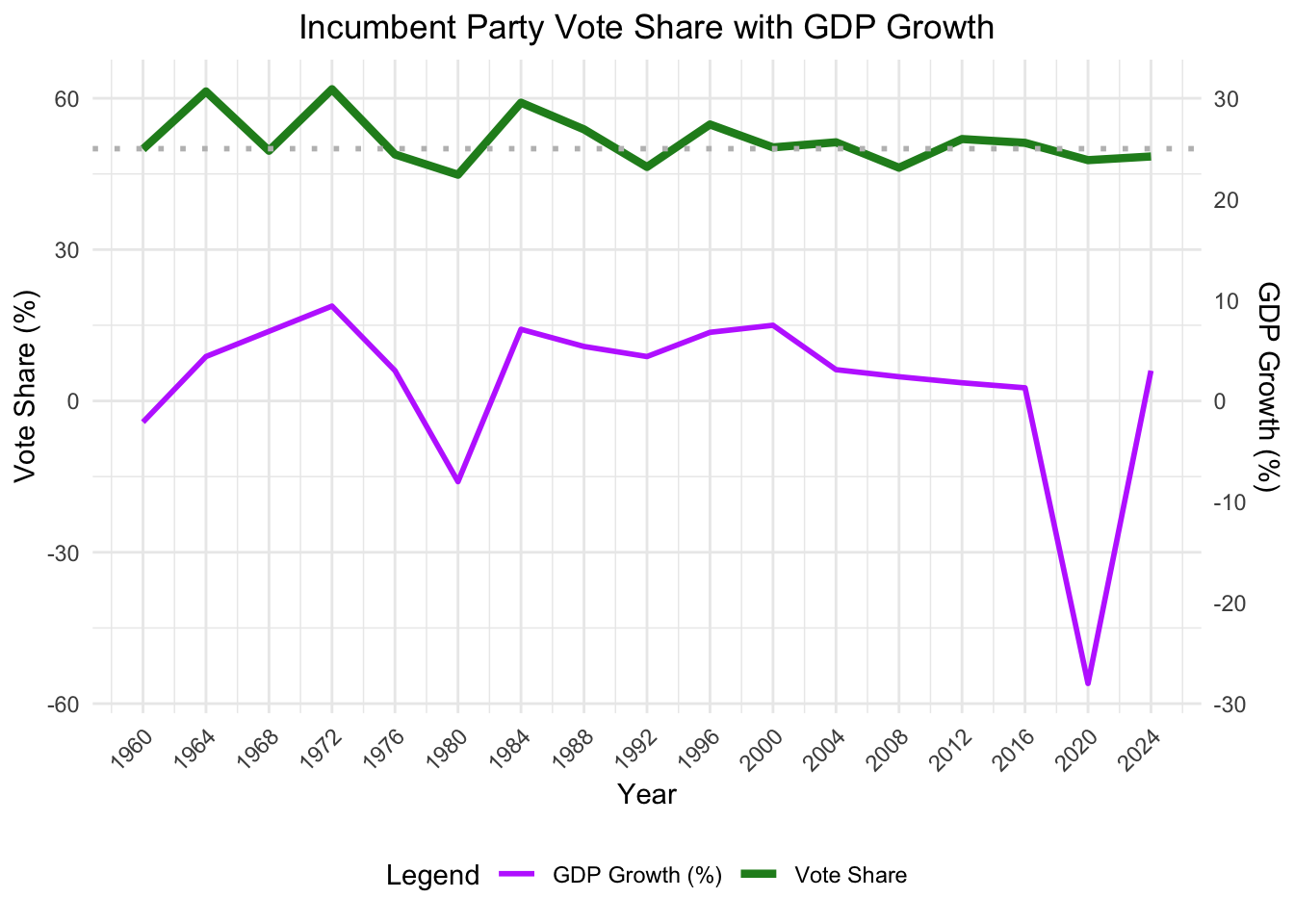

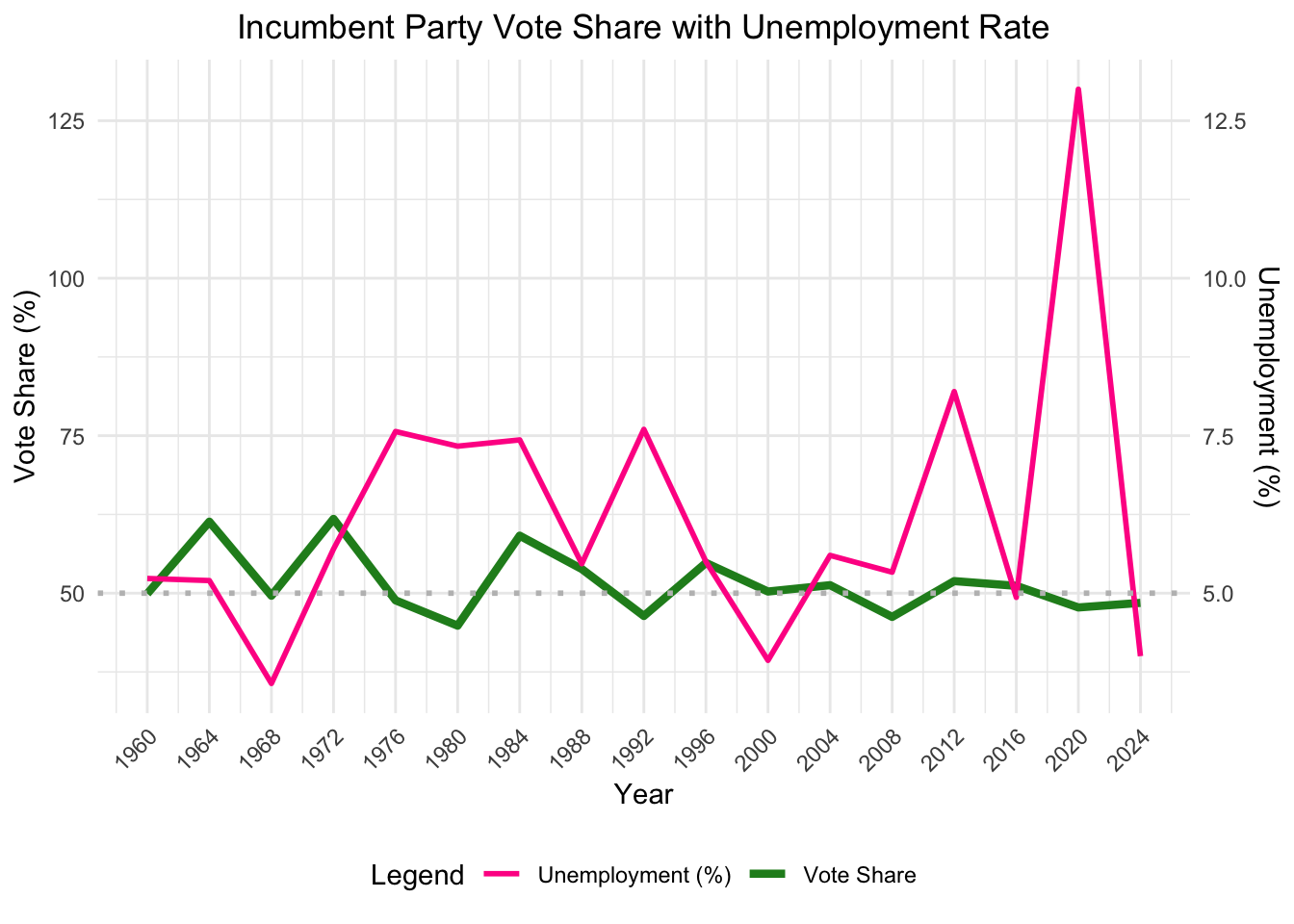

These graphs above help visualize the positive correlation between the incumbent party vote share and GDP growth, as well as the negative correlation between the incumbent party vote share and unemployment rate in the second quarter of the election year. The two-party presidential popular vote share is predicted to be 48.46%, with a 95% confident that the predicted vote share is between 42.94% and 51.57%.

However, the model’s effectiveness is limited. The mean-squared value of 13.14 indicates that the average difference between my prediction and true vote share in this case would be around 3.63 percentage points. Similarly, both the Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation error and the 1000-Fold Cross-Validation error are 27.11, indicating an average prediction error of over 27.11 percentage points, which is relatively high, given that vote shares range from 0 to 100. These evaluation metrics reveal that while the economic indicators used matter, they do not capture the full picture. Other factors—such as social, political, or dynamics of political campaign—might play a larger role in determining election outcomes.

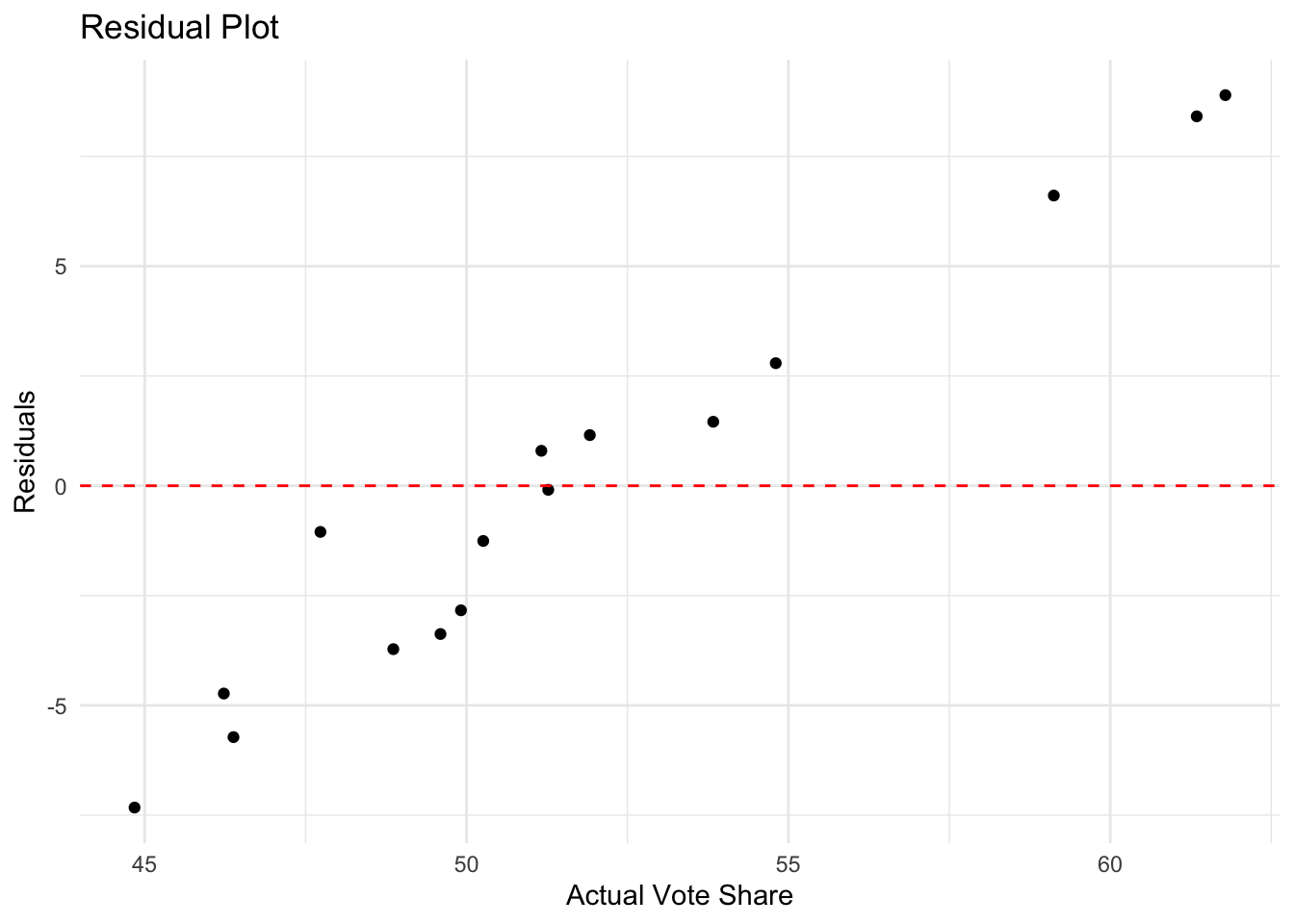

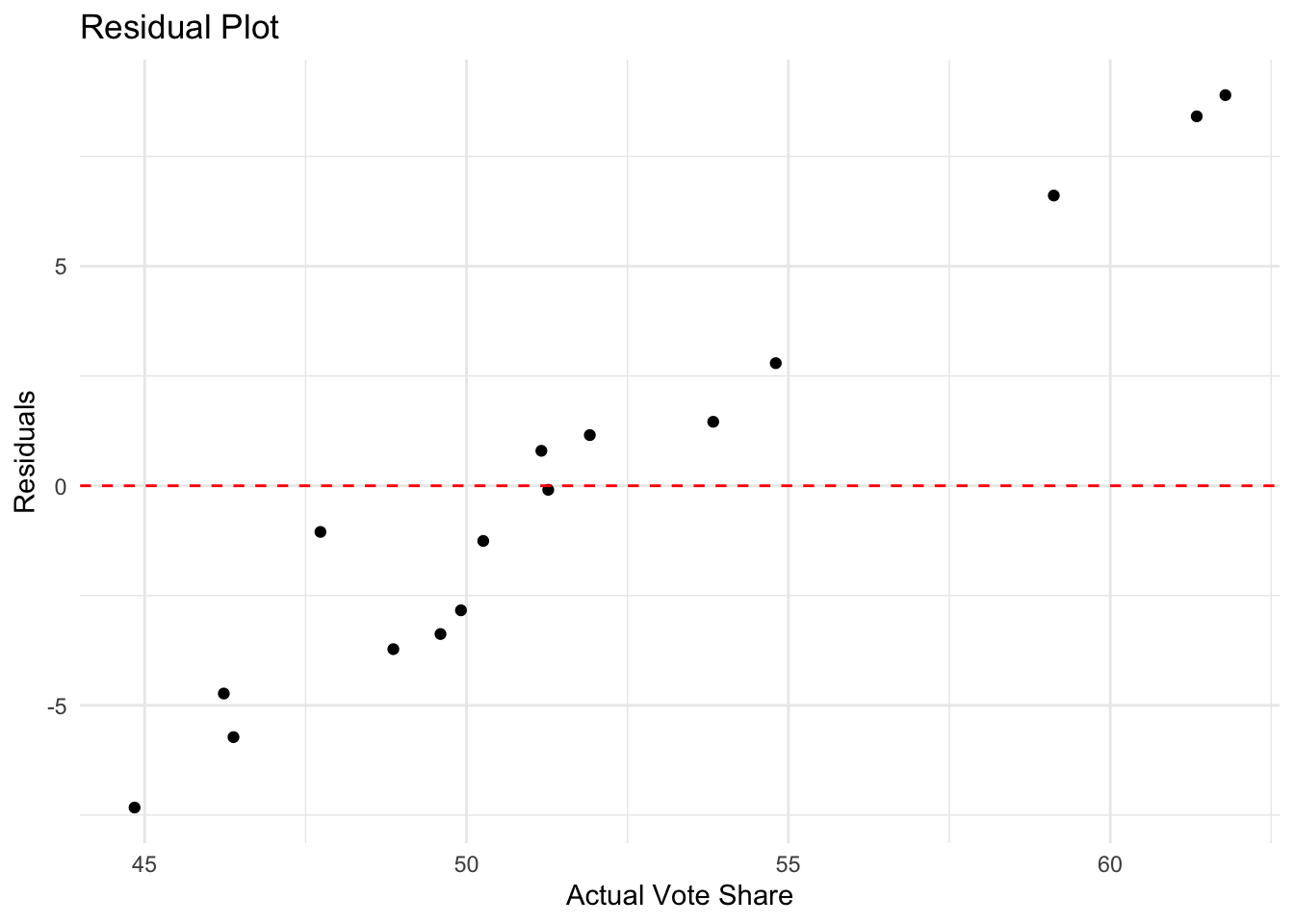

Referring to the residuals plot above, the model underestimates the vote share when the actual vote share is low and overestimates it when the actual vote share is high. This implies that the relationship between the economic indicators and vote share is more complex than the model can account for.

Implication for democracy

Of the numerous variables that can be used to predict elections, the economy is a fundamental variable associated with voters’ judgment of a politician’s capability. As a result, the focus on economic policies especially nearing the election period raises concerns about the short-term manipulation of economic conditions to win votes. Politicians may be motivated to implement policies that create temporary economic relief, such as subsidies or tax cuts, which may boost immediate voter satisfaction. However, these policies could result in long-term financial instability, increasing national debt, and reducing government expenditures in critical areas like education and healthcare. This form of economic populism harms democratic accountability, as voters may make decisions based on recent economic conditions rather than long-term national well-being.

Is this healthy for democracy? The main issue is that the incentives of voters and politicians diverge. While politicians are motivated to win elections, often by delivering short-term gains, voters, in theory, should be prioritizing policies that ensure sustainable growth and stability. As voters, we should better understand how the economy works and hold politicians accountable for their promises, balancing short-term gains with long-term economic development.

Individual vs sociotropic considerations

compare state-level gdp and unemployment level predictive accuracy

Code developed with the assistance of ChatGPT.