Election Blog

Week 3: Polling and Public Opinion

Leading up to the 2020 presidential elections, then-President Donald Trump famously claimed on X (formerly Twitter) that he was “winning BIG in all of the polls that matter,” dismissing the rest as “fake.” This raises an important question: can we trust polls to reflect the real state of public opinion?

Polling, explained

Polls are designed to reveal the public’s preferences ahead of an election. They help politicians gauge voter sentiment and allow the public to monitor general trends, which can lend credibility to the election process by reducing the chances of surprise results.

The goal of a poll is to offer an unbiased estimate of the population’s opinion by surveying a large, representative sample. In theory, while some individuals may be at different ends of the extreme when answering polls, these biases should cancel out, and the aggregate result will provide a median estimate that closely reflects the true public opinion.

To further refine this, platforms like FiveThirtyEight aggregate multiple polls. Individual polls can sometimes be biased towards certain populations or parties, for instance, one might overestimate support for a candidate, while another underestimates it. Therefore, aggregating polls helps average out these errors and gives us a clearer picture of the overall voter landscape.

What can we learn from the polling averages over 2020 election cycle?

Though the media often describes certain events as “gamechangers,” such as a candidate giving a notable speech or performing poorly for the presidential debate, political scientists argue that many dynamic campaign elements may not matter as much as the underlying fundamentals.

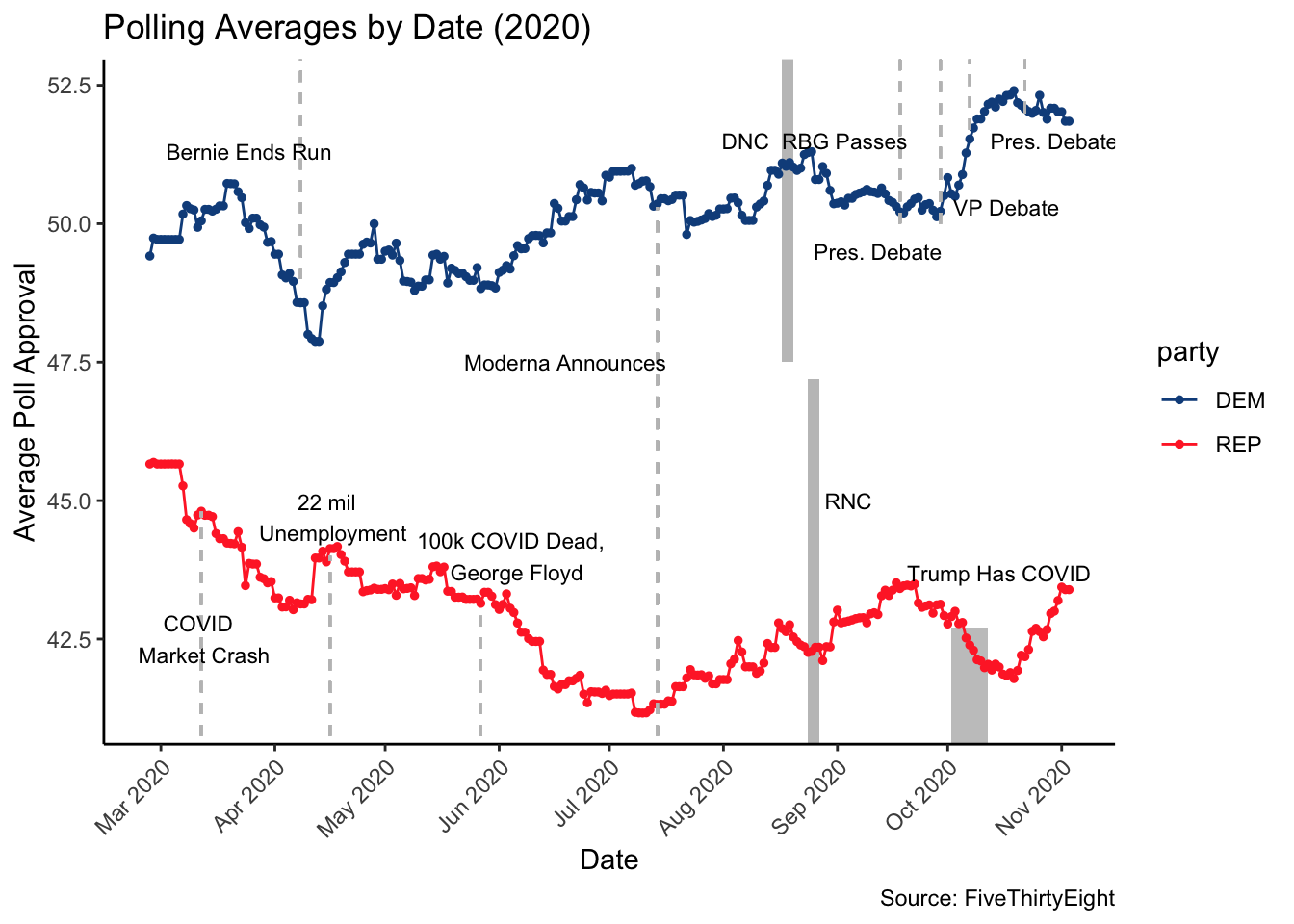

Looking at the graph below of polling averages during the 2020 election cycle, we can see this in action. While there were some expected shifts after key events like the Democratic National Convention (DNC) and the Republican National Convention (RNC), other moments showed surprising results. For example, despite expectations that Trump’s COVID-19 diagnosis might significantly alter support for the Republican party, there was only a modest and short-lived bump in the polling numbers. On the Democratic side, approval fluctuated after events such as Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s passing and the presidential debates, but there wasn’t a dramatic shift that persisted. These trends suggest that even though certain events are billed as “gamechangers,” their actual impact on polling is often limited or unpredictable, leaving many fluctuations unexplained by these moments alone.

Predicting 2024 election outcome using national polling data

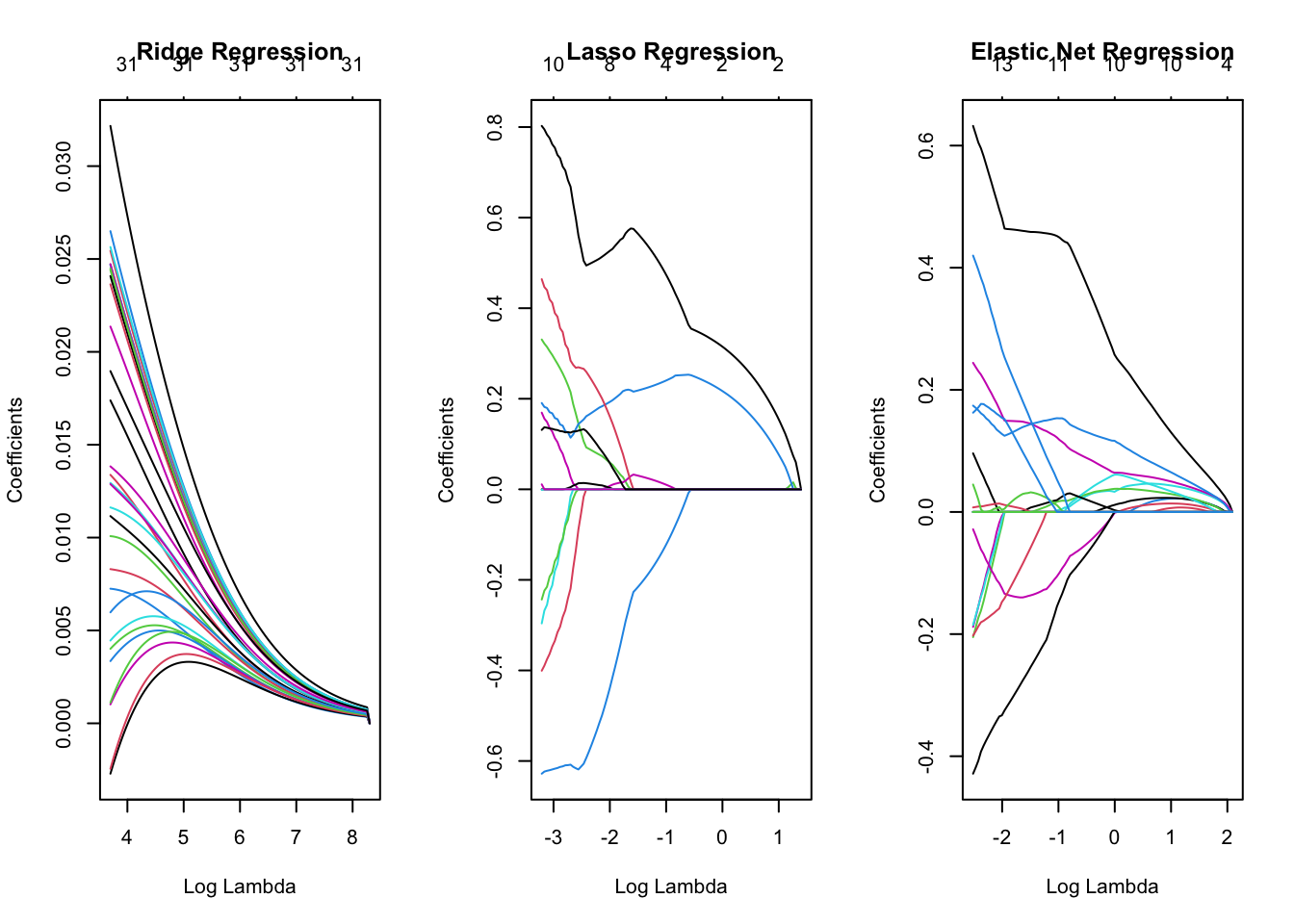

To predict the 2024 election outcome, I will use the regularized regression methods, namely Ridge, Lasso, and Elastic Net. The regression plots below demonstrates how the coefficients for each variable (polling data from various weeks leading up to the election) change as I adjust the regularization strength (lambda) in each method. Ridge shows that all variables are kept in the model, though their influence decreases as lambda increases. Lasso reveals that some coefficients are driven to zero as lambda increases, indicating that certain weeks’ polling data may not be as relevant. Elastic Net Regression offers a middle ground, where some coefficients are reduced to zero, but others are merely shrunk.

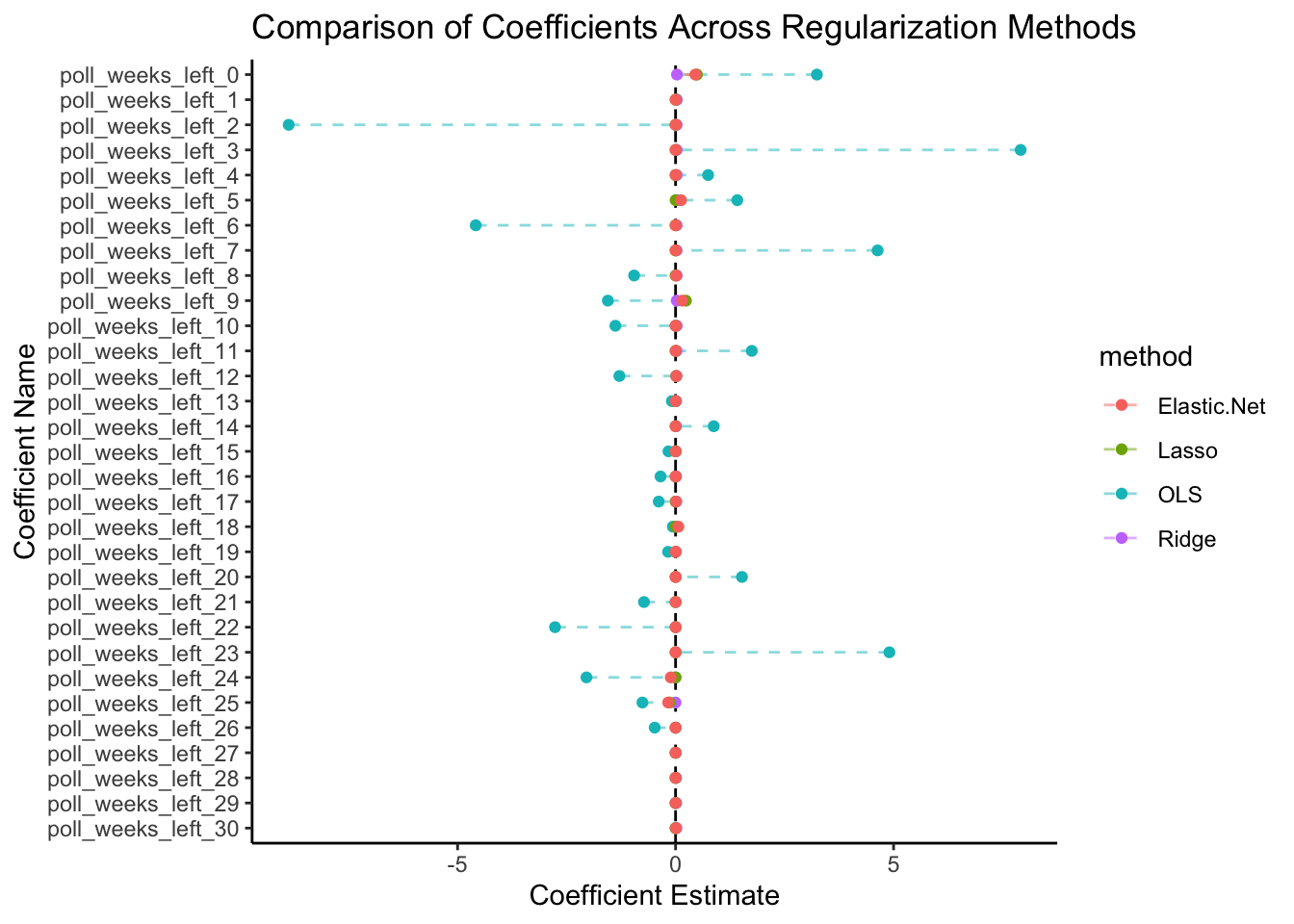

The graph below compares the estimated coefficients across different methods. This gives an overview of which predictors (polling weeks) are most consistently influential in predicting the election outcome across various methods. Based on my analysis, I have predicted:

| Candidate | Predicted Two-Party Vote Share (%) |

|---|---|

| Kamala Harris | 50.59019 |

| Donald Trump | 49.40981 |

These predictions are derived from polling data up to 30 weeks before the election trained on historical data from the election in 1968 to the most recent one in 2020, using Elastic Net regression for its balance between feature selection and regularization. However, my prediction of Harris receiving 50.6% of the popular vote and Trump 49.4% has a margin of error, as reflected in the MSE of 4.38, which means the average difference between my prediction and true vote share in this case would be around 2.1 percentage points.

How do state-level polls differ from national level polls?

While national level polls may not perfectly explain election results, can state-level polls can provide more granular insights into voter preferences and behavior? Each state is a unique battleground in U.S. elections due to the electoral college system. Therefore, state-level polls offer a closer approximation to how individual states may swing, allowing for a finer understanding of electoral outcomes.

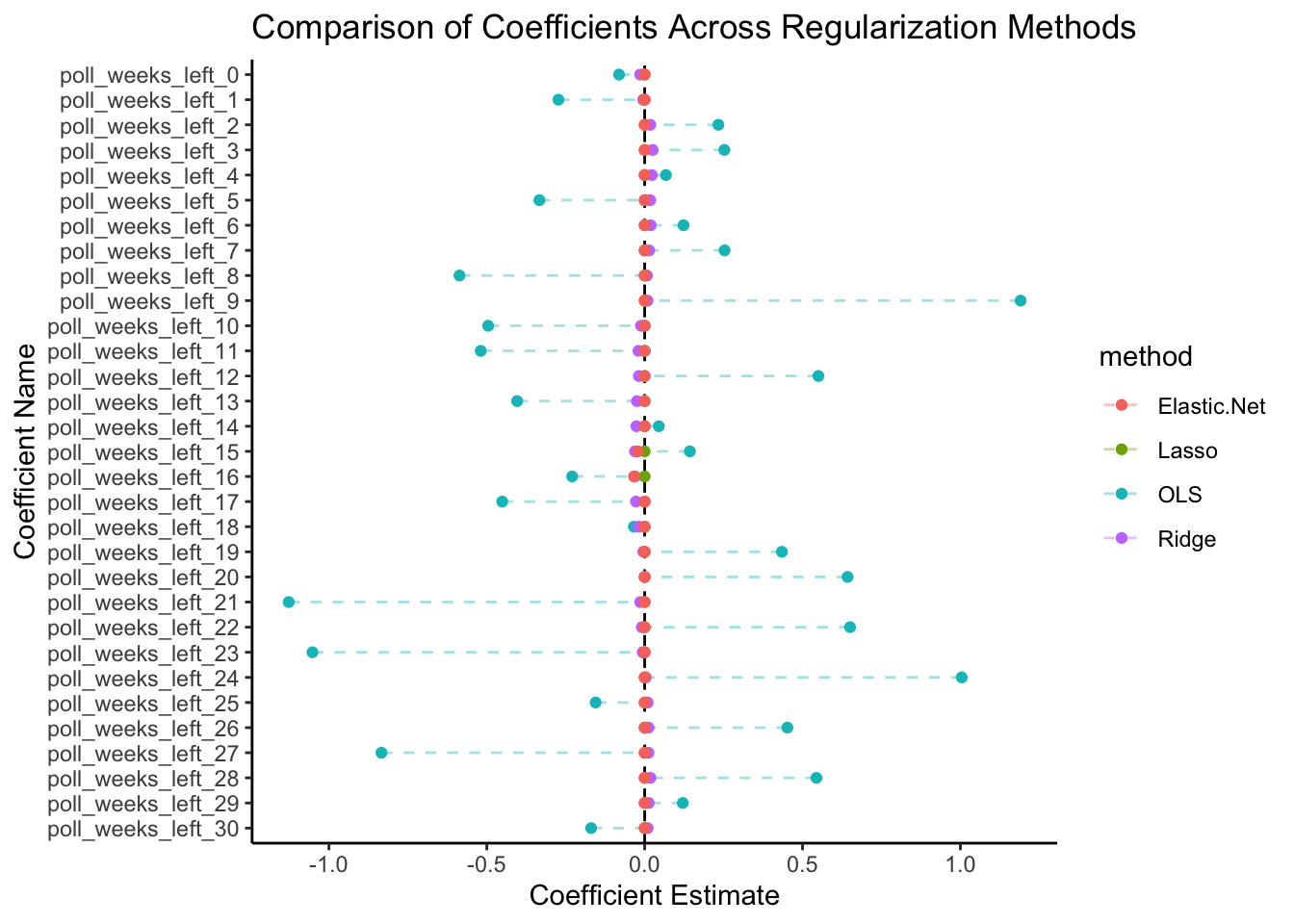

To demonstrate this, I used state-level polling data to build a predictive model for the 2024 presidential election using regularized regression methods. The regression plots visualizes the coefficients estimated for each of the weeks leading up to the election across different regression methods: OLS, Ridge, Lasso, and Elastic Net, using polling data from 1972 to 2020.

I decided to use Elastic Net regression for prediction, as it yielded the most consistent coefficient estimates, accounting for the complexity in the data without overfitting.

| Party | Year | State | Predicted Two-Party Vote Share (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DEM | 2024 | Arizona | 50.37588 |

| REP | 2024 | Arizona | 49.62412 |

| DEM | 2024 | California | 55.49691 |

| REP | 2024 | California | 44.50309 |

| DEM | 2024 | Florida | 50.08302 |

| REP | 2024 | Florida | 49.91698 |

| DEM | 2024 | Georgia | 50.32485 |

| REP | 2024 | Georgia | 49.67515 |

| DEM | 2024 | Maryland | 51.42244 |

| REP | 2024 | Maryland | 48.57756 |

| DEM | 2024 | Michigan | 50.09340 |

| REP | 2024 | Michigan | 49.90660 |

| DEM | 2024 | Minnesota | 50.55983 |

| REP | 2024 | Minnesota | 49.44017 |

| DEM | 2024 | Missouri | 49.42162 |

| REP | 2024 | Missouri | 50.57838 |

| DEM | 2024 | Montana | 50.00000 |

| REP | 2024 | Montana | 50.00000 |

| DEM | 2024 | Nebraska Cd 2 | 50.00000 |

| REP | 2024 | Nebraska Cd 2 | 50.00000 |

| DEM | 2024 | Nevada | 50.37364 |

| REP | 2024 | Nevada | 49.62636 |

| DEM | 2024 | New Hampshire | 50.60594 |

| REP | 2024 | New Hampshire | 49.39406 |

| DEM | 2024 | New Mexico | 50.43592 |

| REP | 2024 | New Mexico | 49.56408 |

| DEM | 2024 | New York | 49.53195 |

| REP | 2024 | New York | 50.46805 |

| DEM | 2024 | North Carolina | 50.38951 |

| REP | 2024 | North Carolina | 49.61049 |

| DEM | 2024 | Ohio | 49.07750 |

| REP | 2024 | Ohio | 50.92250 |

| DEM | 2024 | Pennsylvania | 50.38417 |

| REP | 2024 | Pennsylvania | 49.61583 |

| DEM | 2024 | Texas | 49.34849 |

| REP | 2024 | Texas | 50.65151 |

| DEM | 2024 | Virginia | 50.36907 |

| REP | 2024 | Virginia | 49.63093 |

| DEM | 2024 | Wisconsin | 50.29992 |

| REP | 2024 | Wisconsin | 49.70008 |

An MSE of 70.41 indicates that, on average, the model’s predictions deviate from the actual vote share by about 8.4 percentage points. This error in predicting vote share could mean missing whether a state swings to a particular party, especially in battleground states where races are often decided by margins of 1-2%.

Insights from Silver and Morris

Nate Silver was a key figure behind FiveThirtyEight, one of the largest election forecasting platforms in recent election cycles, which is now led by Elliot Morris. Their contrasting perspectives on the roles of fundamentals (economic forces and demographic information) versus poll-based forecasts provide valuable insights into election prediction.

Nate Silver (2024) takes a more case-by-case approach to election prediction. He emphasizes the importance of accounting for specific events and conditions that may impact an election. For instance, he considered the unique influence of COVID-19 during the 2020 presidential elections and has since decided to remove those considerations as we transition from a pandemic to an endemic state. He also highlights the potential effects of independent candidates, like Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who recently suspended his presidential campaign. Additionally, Silver points out that with Biden (who has dropped out and been replaced by Harris) and Trump potentially facing off again, examining historical data from past presidential rematches becomes essential. This granularity in analysis ensures that all factors specific to the election year, particularly those affecting the candidates and significant societal changes, are adequately considered.

Elliot Morris (2024), on the other hand, adopts a big-picture perspective in his forecasting model. He integrates polling averages—assigning different weights and scores to various pollsters—with fundamental data that captures the economic landscape, such as employment rates, consumer spending, inflation, and political metrics like presidential approval ratings. This combination allows Morris to provide a more holistic view of the electoral landscape.

Silver’s focus on depth and Moris’s comprehensive coverage of breadth brings me to a novel idea: what if we approached election predictions from an individual or micro-level perspective? Imagine a perfect world where we could obtain any information from voters, except for who they will actually vote for on election day. In such a scenario, we could segment voters based on their behaviors and motivations:

- Partisan Voters: These individuals would support their party regardless of candidate or any “game-changing” moments.

- Candidate-Centric Voters: A smaller group, who decide based on the individual candidate rather than party affiliation.

- Challenger Voters: Voters who lean towards challengers when dissatisfied with current economic and social conditions, driven by a desire for change.

- Swing Voters: Those who fluctuate between parties based on specific issues or candidate qualities.

- Situational Voters: Their likelihood to show up could depend on various circumstances, such as pressing issues or the overall campaign dynamics.

If we could quantify these segments, we might be able to predict election outcomes accurately. However, this perfect world with perfect information lives only in our imagination, much like the ideal of a perfect democracy. In reality, voters’ motivations are complex, often influenced by emotions, misinformation, and social dynamics that are difficult to quantify. While we may never achieve that perfect clarity, this attempt to understand voters’ decision-making process can offer insights to how democracy works in practice.

Code developed with the assistance of ChatGPT.