Election Blog

Week 4: Incumbency, Strategy, Democracy

What’s exciting about the 2024 presidential election is the unique matchup: Kamala Harris, the current vice president, facing Donald Trump, a former president from one term ago. This scenario challenges traditional theories of incumbency advantage. Political scientists often argue that incumbent presidents are more likely to perform well in re-elections due to institutional advantages. On the other hand, incumbent parties, without a sitting president, tend to suffer from mean reversion.

In the 2024 race, however, both candidates complicate these dynamics. Trump is technically a former president, but as he is not the immediate incumbent, does he still benefit from the same advantages? And what about Harris, the vice president of the current administration? These overlapping roles blur the lines of incumbency, making it much harder to predict the election outcome.

Incumbency

Out of 12 post-World War II elections where at least one incumbent was running for re-election, a significant 66.67% resulted in victories for the incumbent presidents. Specifically, incumbents from both the Democratic and Republican parties claimed victory in 8 of these instances, showcasing voter preference over those who already hold office. These statistics reveal that incumbent presidents are typically at an advantage, be it through name recognition, public attention through media coverage, headstart in campaigning without the concern of primary elections, and power for pork-barrel spending.

| Statistic | Value |

|---|---|

| Elections with At Least One Incumbent Running | 12 |

| Incumbent President Victories | 8 |

| Incumbent President Victories (Percentage) | 66.67% |

While incumbent presidents often enjoy an advantage in re-election campaigns, incumbent parties face a different reality. As the data shows, both the Democratic and Republican parties have seen incumbents win elections in the post-World War II era only for 47.37% of the time. This can be explained by mean reversion, the idea that when a political party performs unusually well in one election, it tends to return to its average performance in the next. For example, an incumbent party may win during a period of high economic growth or due to a scandal of the opposition party. In such a year, the incumbent party may win states or voters they might not have in a typical election cycle. However, the next time that incumbent party runs, without the unique circumstances that led to their initial overperformance, they are likely to revert to their historical average performance.

| Incumbent Party Wins in Presidential Elections | Value |

|---|---|

| Democratic Party | 4 |

| Republican Party | 5 |

| Democratic + Republican | 9 |

| Total Incumbent Party Wins | 47.37% |

Several candidates, including Richard Nixon (1968) and George H.W. Bush (1988), were part of the previous administration and won the election. Nixon lost in 1960 but returned to win in 1968 after serving as vice president under Eisenhower. This highlights how losing once does not eliminate a candidate’s chances later, which may be the case for Trump. Bush served as vice president under Reagan, and his victory in 1988 is a classic case of an incumbent party benefiting from a popular outgoing president. On the contrary, all candidates from the Democratic Party, including Walter Mondale (1984), who served as vice president under Jimmy Carter, Al Gore (2000), the vice president to Bill Clinton, and Hillary Clinton (2016), the Secretary of State under Obama’s administration, lost their bids. It is worth noting that both Al Gore and Hillary Clinton won the national popular vote share but lost the electoral college.

| Year | Party | Candidate | Previous Administration | Winner |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1960 | REP | Nixon, Richard M. | TRUE | FALSE |

| 1968 | REP | Nixon, Richard M. | TRUE | TRUE |

| 1984 | DEM | Mondale, Walter | TRUE | FALSE |

| 1988 | REP | Bush, George H.W. | TRUE | TRUE |

| 2000 | DEM | Gore, Al | TRUE | FALSE |

| 2016 | DEM | Clinton, Hillary | TRUE | FALSE |

Will the incumbency advantage apply to Harris or Trump in 2024? Well, it is complicated.

Although Harris, currently serving as vice president, may carry some advantage (think Bush riding Reagan’s popularity in 1988), it’s not a guaranteed win. Just look at Al Gore (2000) or Walter Mondale (1984), both of whom lost despite being vice presidents. Harris faces the challenge of not holding the full “incumbency” title, so she won’t fully benefit from the positive economic conditions or popular policies of the last four years, such as the Inflation Reduction Act or proposals for student loan forgiveness. Apart from this, running as the vice president means she could inherit the baggage of the current administration, whether that’s inflation or negative sentiment around Biden’s policies.

Trump, on the other hand, is a former president, which makes his case unique. He’s not the incumbent, but his one-term-ago status gives him advantages, including name recognition and a fiercely loyal base. But Trump’s 2020 loss suggests that voters might not view him as favorably as they did in 2016. Historically, Americans have been hesitant to re-elect presidents they have already rejected. Grover Cleveland is the only president in modern U.S. history to win a non-consecutive term.

Overall, neither Harris nor Trump perfectly fit the typical “incumbency advantage” model.

Strategy

One of the reasons for the incumbent president’s advantage is their “power of proposal,” where they can direct agencies to allocate federal aid, either equitably to all constituents, to reward co-partisans in core states, or to target electorally important constituents in swing states. The latter two strategies are known as pork-barrel spending, a term derived from the practice of storing pork fat in barrels to preserve it, symbolizing how resources are saved or allocated to sustain political power and influence.

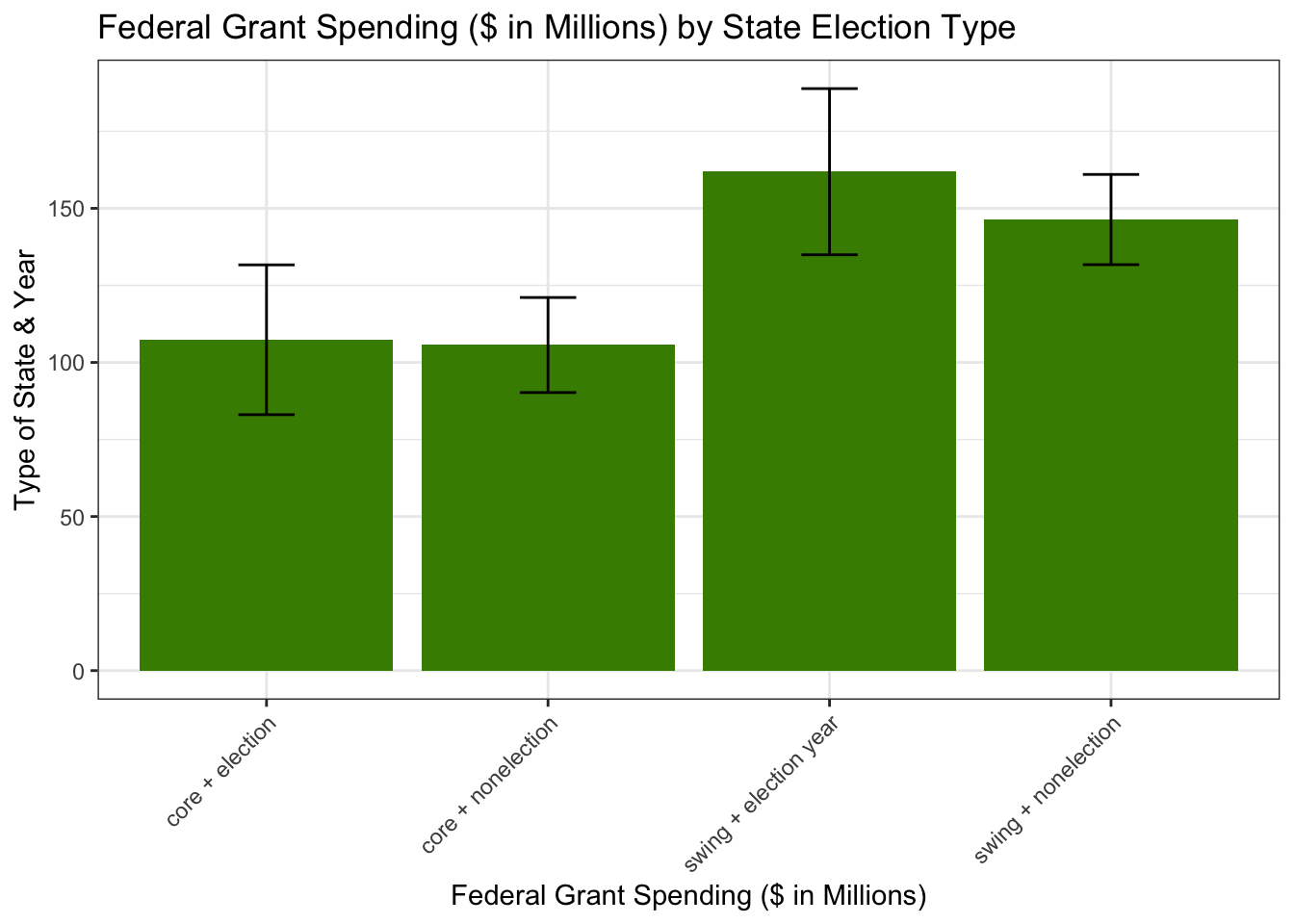

As shown in the graph below, presidents spend significantly more federal grants in swing states during election years, while core states tend to receive the least funding in non-election years. This suggests that selective fund allocation is vital in ensuring the incumbent’s success in re-election.

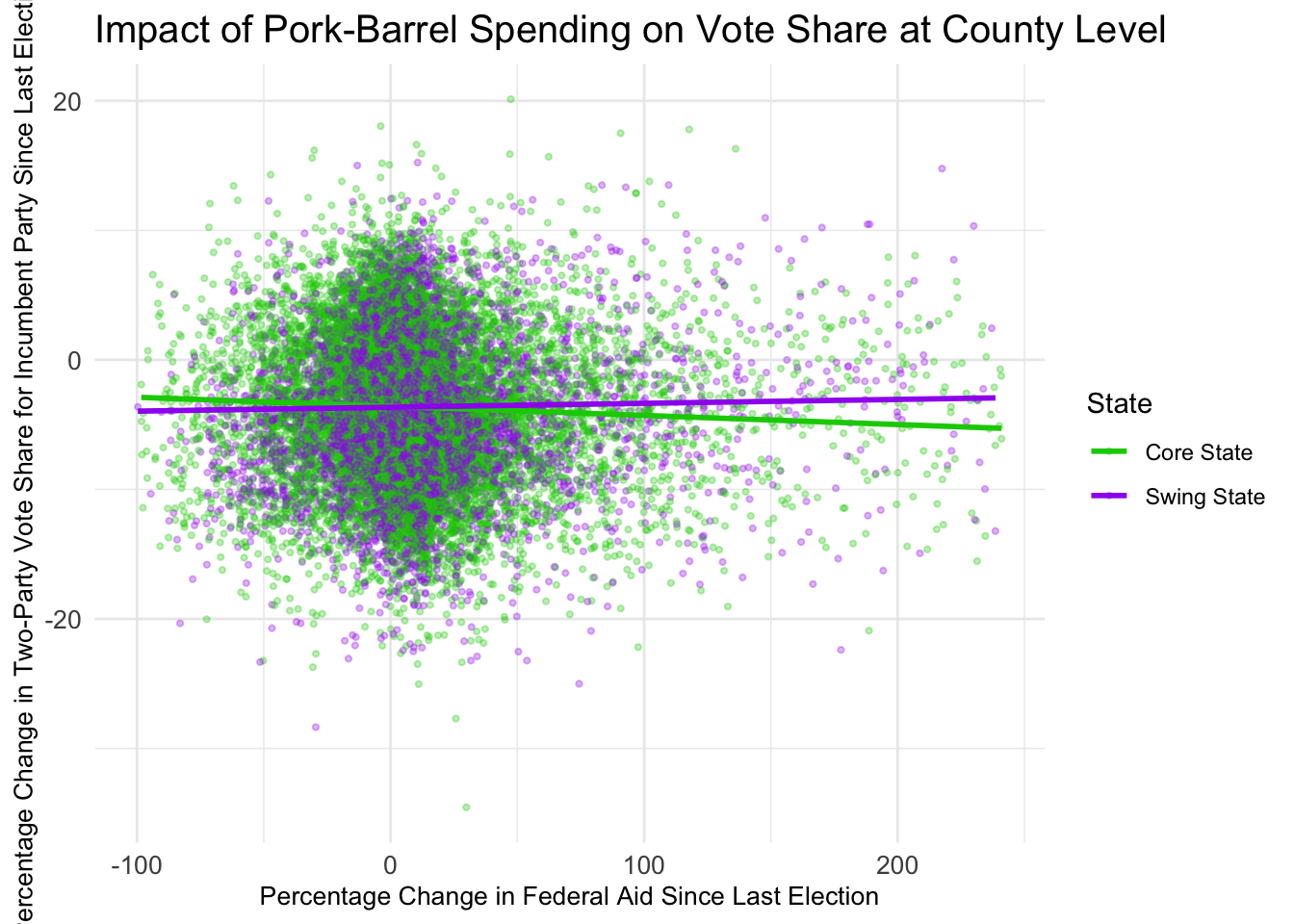

While the graph below demonstrates that pork buys incumbency advantage at a county level, this advantage seems to be stronger in swing states.

To verify the interaction between these two variables, I used a different slopes model to estimate the coefficients. The table below reveals that core states show a baseline decline for incumbents when aid remains unchanged. The intercept estimate of -6.485 indicates that, in core states, when there is no change in federal aid since the last election, the two-party vote share for the incumbent party will decline by 6.485 percentage points compared to the last election, assuming that other factors (including year, percentage change in county-level per capita income, incumbent’s margin in TV ad airings in state, incumbent’s margin in campaign appearances in state, and change in county population 1 year before election) remain constant. On average, for every 1 percentage point increase in federal aid to counties in core states, the incumbent’s vote share increases by 0.004 percentage points compared to the last election.

Whereas in swing states, when there is no change in federal aid, the two-party vote share for incumbent party decreases by -6.377 percentage points compared to last election. holding the same other factors the same. When federal aid increases by 1 percentage point in swing states, the incumbent’s vote share rises by 0.01 percentage points compared to last election on average.

| Term | Estimate | Std. Error | t-value | p-value | Lower CI | Upper CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| intercept | -6.485 | 0.085 | -76.177 | 0.000 | -6.652 | -6.318 |

| dpct_grants | 0.004 | 0.001 | 3.819 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.006 |

| comp_state | 0.108 | 0.077 | 1.402 | 0.161 | -0.043 | 0.259 |

| as.factor(year): 1992 | -0.062 | 0.119 | -0.524 | 0.600 | -0.296 | 0.171 |

| as.factor(year): 1996 | 6.230 | 0.120 | 51.944 | 0.000 | 5.995 | 6.466 |

| as.factor(year): 2000 | -2.009 | 0.119 | -16.880 | 0.000 | -2.242 | -1.775 |

| as.factor(year): 2004 | 8.172 | 0.117 | 69.715 | 0.000 | 7.942 | 8.402 |

| as.factor(year): 2008 | 3.329 | 0.121 | 27.488 | 0.000 | 3.091 | 3.566 |

| dpc_income | 0.148 | 0.022 | 6.654 | 0.000 | 0.104 | 0.192 |

| inc_ad_diff | 0.059 | 0.011 | 5.386 | 0.000 | 0.037 | 0.080 |

| inc_campaign_diff | 0.162 | 0.013 | 12.295 | 0.000 | 0.136 | 0.188 |

| dpct_popl | 1.659 | 0.529 | 3.136 | 0.002 | 0.622 | 2.696 |

| dpct_grants:comp_state | 0.006 | 0.002 | 3.624 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.010 |

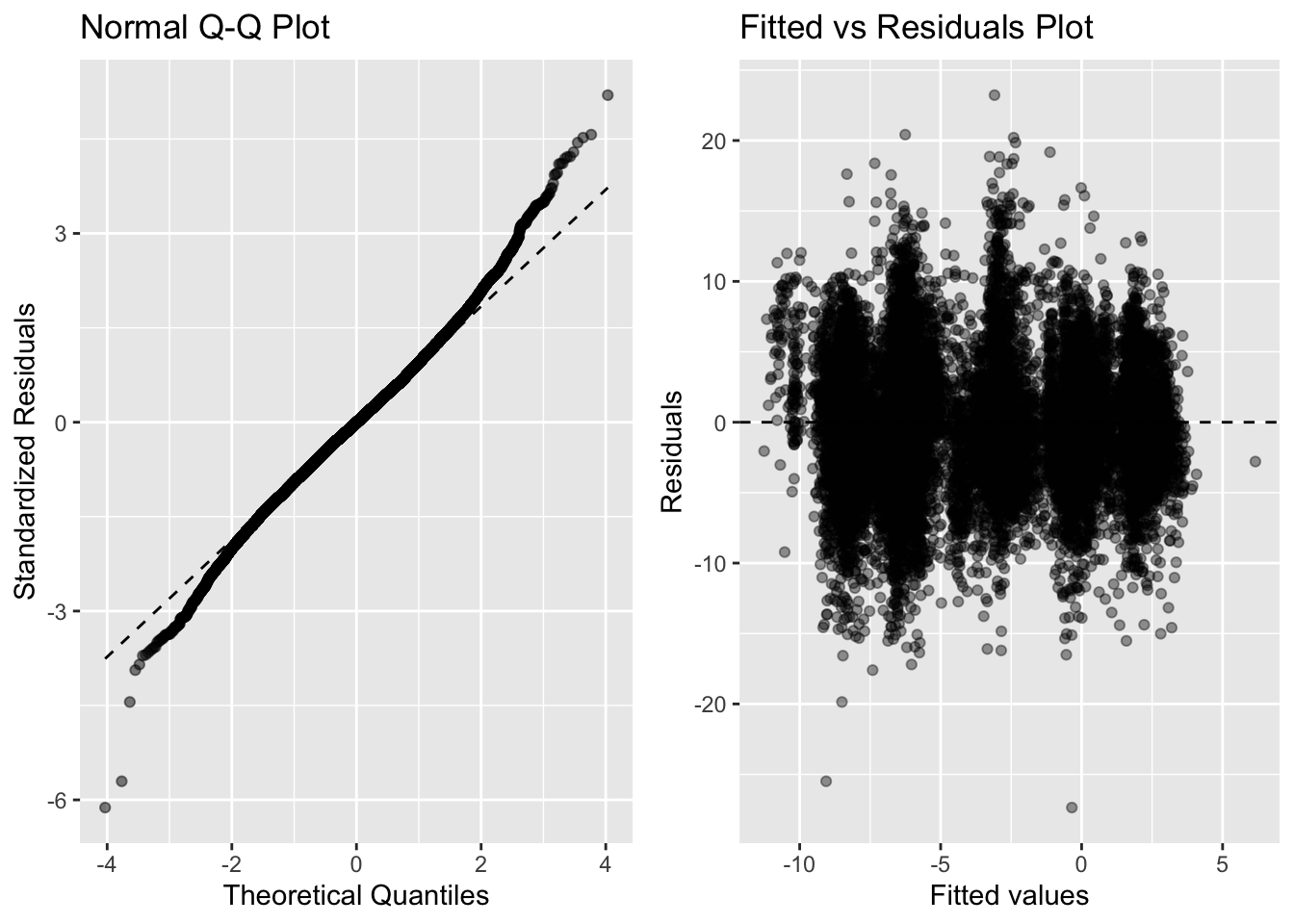

Based on the QQ-plot, the residuals of the model seem to be roughly normally distributed. While the residuals might be a bit larger at certain fitted values, there is mostly-constant variance. Overall, I will assume that this linear regression model is valid.

Democracy

Is this an undesirable feature of a democratic system? While pork-barrel spending might seem like a tactic for politicians to buy votes, voters could also be seen as rewarding politicians for improving their communities through projects like disaster relief and building infrastructure.

Ultimately, transparency and accountability are key. Incumbents should be held to high standards, ensuring that their use of public funds is motivated by genuine community needs rather than electoral gain. A solution is to strengthen oversight and reporting requirements through independent audits and public spending reports, taking Canada’s Office of the Auditor General as an example. Limiting discretionary spending or implementing spending moratoriums during election periods, such as the caretaker conventions in Australia, also reduce opportunities for incumbents to manipulate public opinion by channeling resources into politically important regions, like swing states, or rewarding loyal supporters in core states.

Code developed with the assistance of ChatGPT.