Election Blog

Week 5: Who Votes, and How Do They Vote? An Overview of Demographics

In an increasingly polarized nation, or as Lynn Vavreck coined it, “calcified,” demographics have become more predictive in understanding voting patterns.

Who Votes?

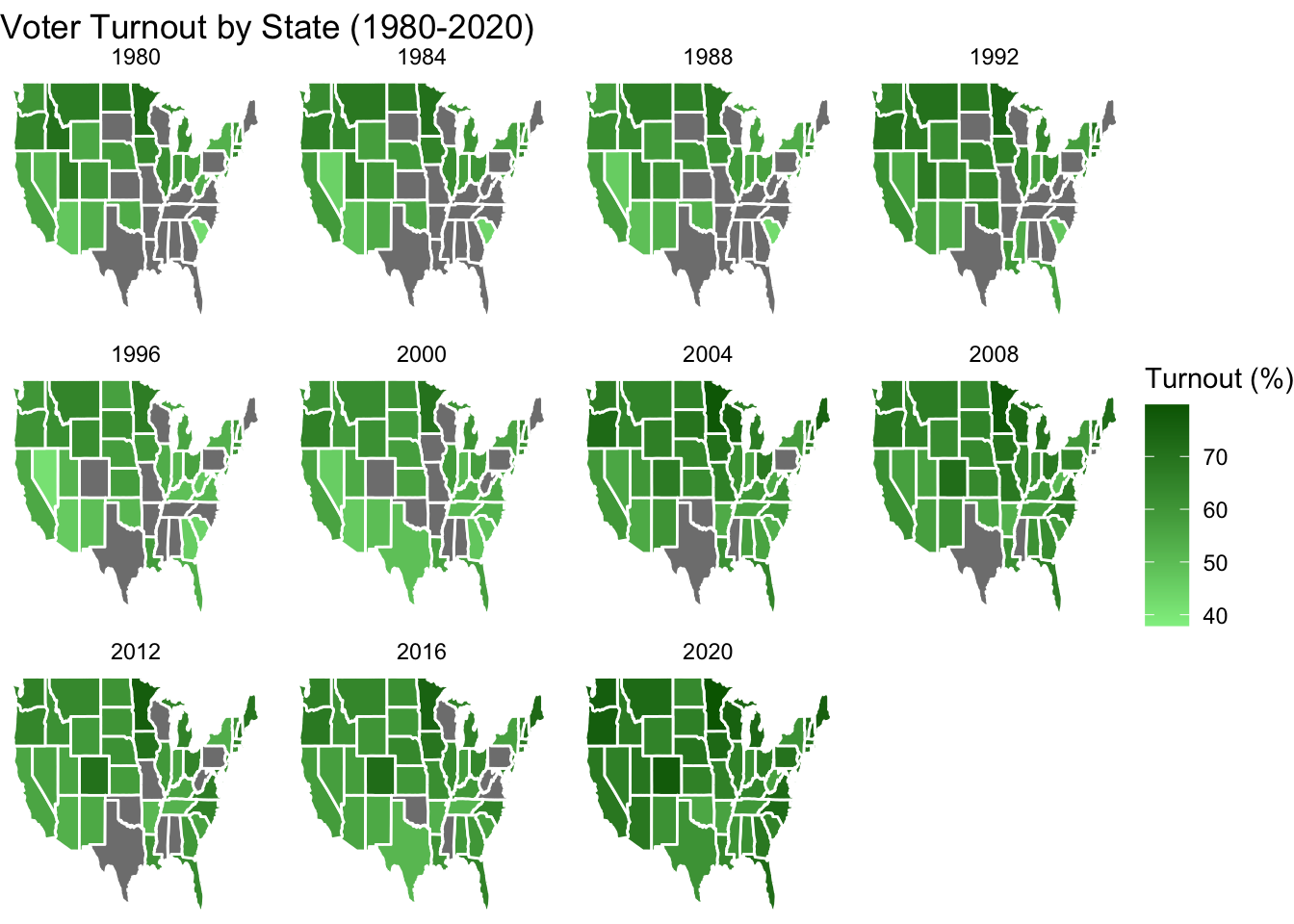

Not every single citizen is registered to vote, and not every registered voter will turnout. The graph below shows the voter turnout in different states in the presidential elections from 1980 to 2020.

Individuals with higher education levels are more likely to vote because education provides information about the democratic process and instills a sense of civic virtue (Wolfinger & Rosenstone, 1980; Shaw & Petrocik, 2020). Older voters, especially retirees, are also more likely to participate due to their interest in preserving government programs like Social Security (Shaw & Petrocik, 2020). Rosenstone & Hansen (1993) also suggest that white and wealthier demographics are more likely to engage in politics and voting generally.

How Do They Vote?

Political scientists widely agree that party affiliation is the most significant predictor of voting behavior, though this piece of information is not always available due to different states’ data collection policies and voters’ choice to disclose themselves as independent. While demographic factors like education level, age, gender, race, and income also play a role, they are generally seen as secondary to party identification.

To explore how well demographic factors predict voting behavior, I built both logistic regression and random forest models using the American National Election Studies (ANES) dataset in 2020. My analysis focuses on core demographics like age, gender, race, education, and income to predict whether someone is likely to vote for the Democratic or Republican candidate in the U.S. presidential election. By comparing the performance of these two models, I aim to identify which method better captures the relationship between voter demographics and vote choice. The logistic regression model offers a more interpretable framework, while the random forest model capture non-linear interactions between explanatory variables to achieve greater predictive accuracy.

| Predictor | Estimate | Std. Error | Z value | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 3.0466894 | 0.3879300 | 7.8537100 | 0.0000000 |

| age30-29 | 0.2605495 | 0.1932560 | 1.3482090 | 0.1775912 |

| age40-49 | 0.2814913 | 0.1971868 | 1.4275362 | 0.1534254 |

| age50-64 | 0.4790822 | 0.1804352 | 2.6551486 | 0.0079273 |

| age65-74 | 0.2513214 | 0.2100600 | 1.1964266 | 0.2315301 |

| age75+ | 0.2873645 | 0.2503041 | 1.1480614 | 0.2509432 |

| ageBelow 18 | 0.4689021 | 0.3298902 | 1.4213885 | 0.1552038 |

| genderFemale | -0.0232485 | 0.0968415 | -0.2400670 | 0.8102783 |

| raceBlack non-Hispanic | -1.8433006 | 0.2820778 | -6.5347237 | 0.0000000 |

| raceHispanic | -0.6179115 | 0.1828442 | -3.3794424 | 0.0007263 |

| raceOther or multiple races, non-Hispanic | 0.0305557 | 0.1661450 | 0.1839099 | 0.8540842 |

| educationHigh school | -0.0752261 | 0.3247652 | -0.2316321 | 0.8168238 |

| educationSome college | -0.0811367 | 0.3121902 | -0.2598953 | 0.7949446 |

| educationCollege+ | -0.8579110 | 0.3130217 | -2.7407398 | 0.0061301 |

| income7-33 percentile | -0.1264412 | 0.1715965 | -0.7368519 | 0.4612124 |

| income34-67 percentile | 0.1473429 | 0.1428070 | 1.0317624 | 0.3021834 |

| income68 to 95 percentile | 0.1106322 | 0.1520675 | 0.7275207 | 0.4669070 |

| income96 to 100 percentile | -0.2014069 | 0.2263415 | -0.8898366 | 0.3735536 |

| religionCatholic | -0.2136832 | 0.1241851 | -1.7206827 | 0.0853084 |

| religionJewish | -0.4982795 | 0.3542658 | -1.4065132 | 0.1595718 |

| religionOther | -0.5680956 | 0.1153176 | -4.9263556 | 0.0000008 |

| attend_churchAlmost every week - often | -0.2095727 | 0.1842234 | -1.1376013 | 0.2552870 |

| attend_churchOnce or twice a month | -0.2023907 | 0.2035687 | -0.9942130 | 0.3201192 |

| attend_churchA few times a year - seldom | -0.2808382 | 0.1827159 | -1.5370211 | 0.1242881 |

| attend_churchNever | -0.7653464 | 0.1438191 | -5.3215916 | 0.0000001 |

| work_statusNot employed | -0.1516865 | 0.1792080 | -0.8464268 | 0.3973147 |

| work_statusRetired | 0.1027262 | 0.1553820 | 0.6611201 | 0.5085353 |

| work_statusHomemaker | 0.1850355 | 0.2223238 | 0.8322796 | 0.4052511 |

| work_statusStudent | -1.4388741 | 0.5425110 | -2.6522484 | 0.0079958 |

| party_identificationIndependent | -2.4964501 | 0.1111003 | -22.4702338 | 0.0000000 |

| party_identificationNo preference; none; neither | -2.3768968 | 1.4335381 | -1.6580632 | 0.0973047 |

| party_identificationOther | -2.2416718 | 0.2383706 | -9.4041439 | 0.0000000 |

| party_identificationDemocrat | -5.2693001 | 0.1612323 | -32.6814216 | 0.0000000 |

In the logistic regression model, several demographic predictors show statistically significant relationships with vote choice. For instance, Black non-Hispanic voters are 84.17% less likely to vote Republican than White non-Hispanic voters, holding other variables constant. Consistent with the literature, people who think of themselves as Democrats are 99.49% less likely to vote Republican than those who identify as Republicans. Students are 76.28% less likely to vote Republican, whereas homemakers are 20.33% more likely to vote Republican, compared to employed individuals. Those who attend church less frequently are significantly less likely to vote Republican compared to those who attend every week regularly. Interestingly, variables like age, gender, education level, and income do not have any meaningful impact on vote choice in this model, as their p-values are above the typical 5% significance level.

The overall accuracy of the logistic model for in-sample predictions is 85.79%, while its out-of-sample accuracy is 86.23%, showing fairly high accuracy.

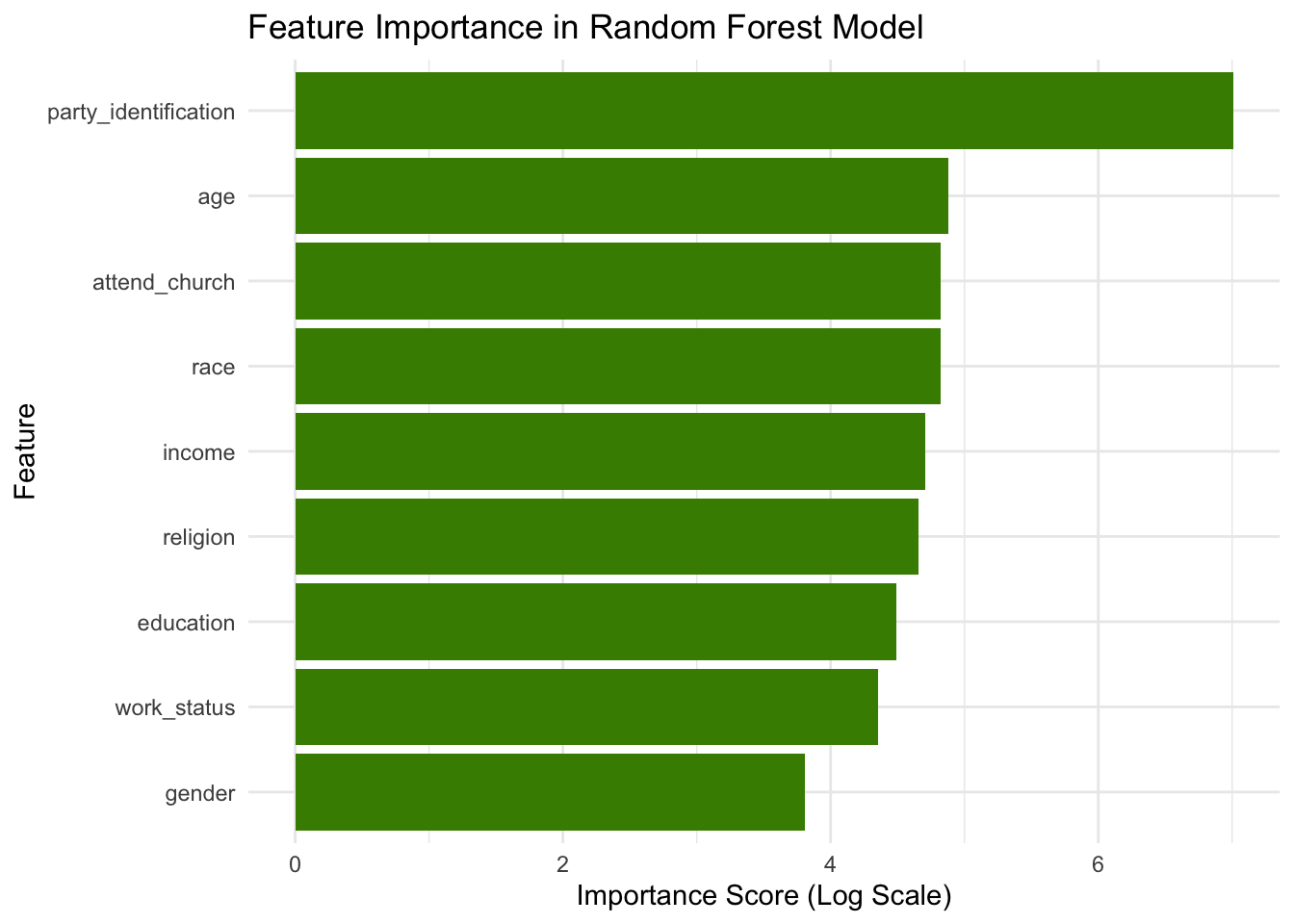

The random forest model is consistent with the logistic regression model in showing that party identification, race, and church attendance are important predictors for an individual’s vote choice. However, the model rated age as fairly important and work status as less important, which differs from the results of the logistic regression model.

For the random forest model, the in-sample accuracy is 84.52% whereas the out-of-sample accuracy stood at 84.77%—slightly lower than the logistic regression model, suggesting that the random forest method may have a poorer predictive performance when considering complex interactions between demographic factors with low model interpretability.

Narrowing down states of interest using expert predictions

As seen in the map above containing expert predictions by Sabato’s Crystal Ball, most states are already categorized as likely or safe for one party. For simplicity, I’ll assume that all electoral votes from these states will go to their predicted party. Although Maine and Nebraska have a different system (allocating electoral votes by congressional district), I will assume their overall votes cancel each other out, as Maine leans Democratic and Nebraska is solidly Republican.

Therefore, I will focus my state-level demographic analysis on the seven battleground states: Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

Using Pennsylvania as an example

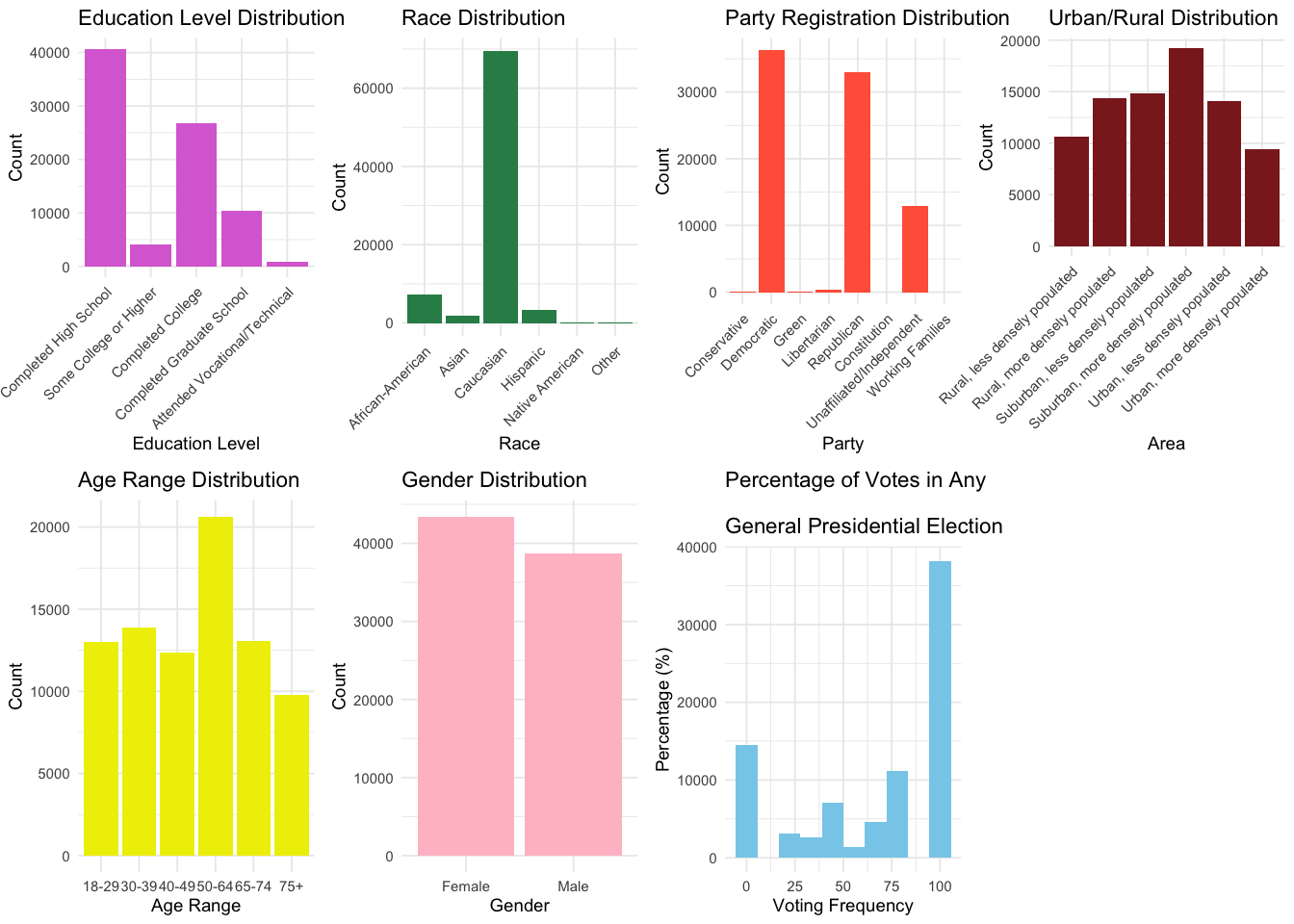

The following plots display the demographic distribution in the state of Pennsylvania as an example, using its 1% voterfile data.

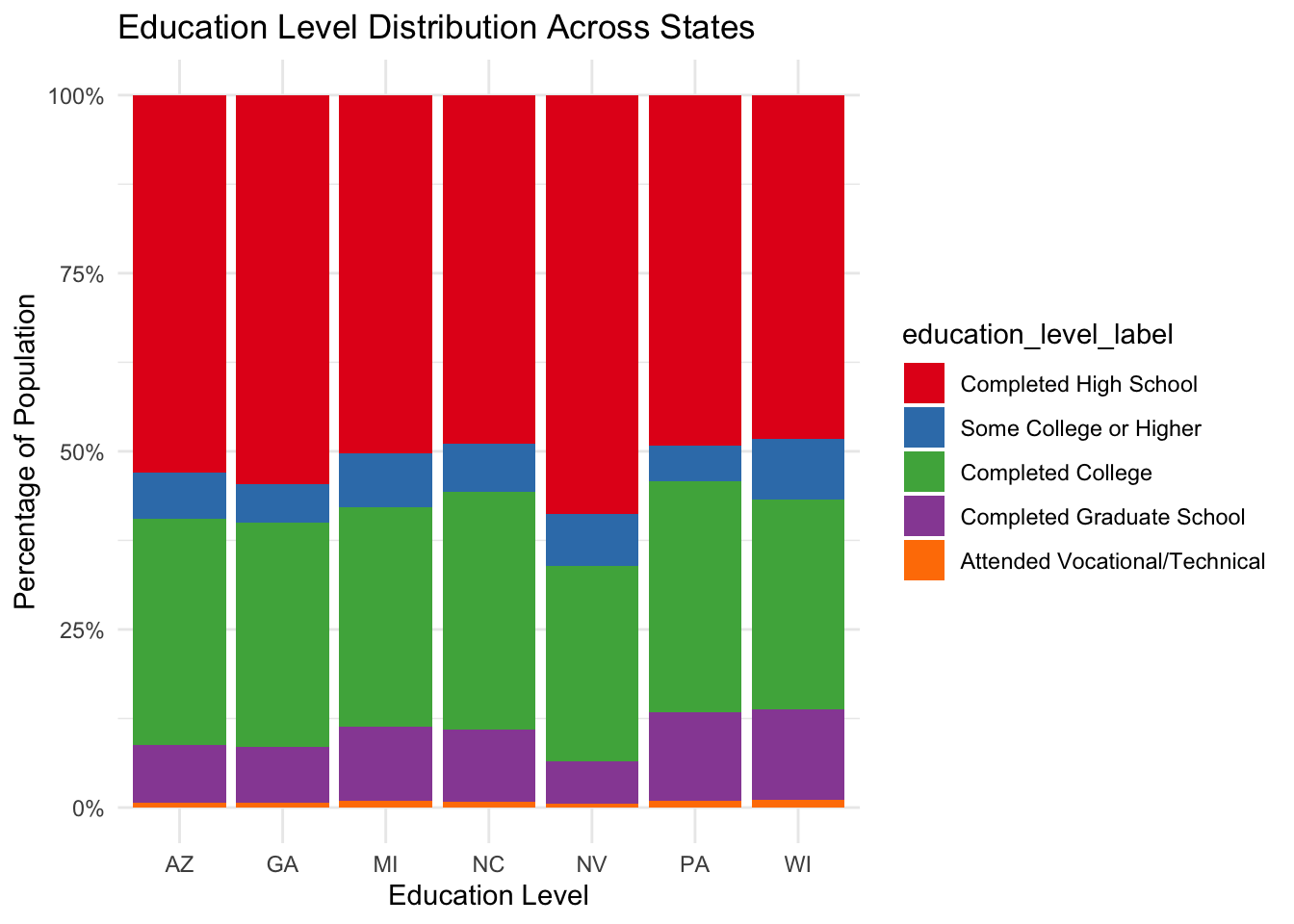

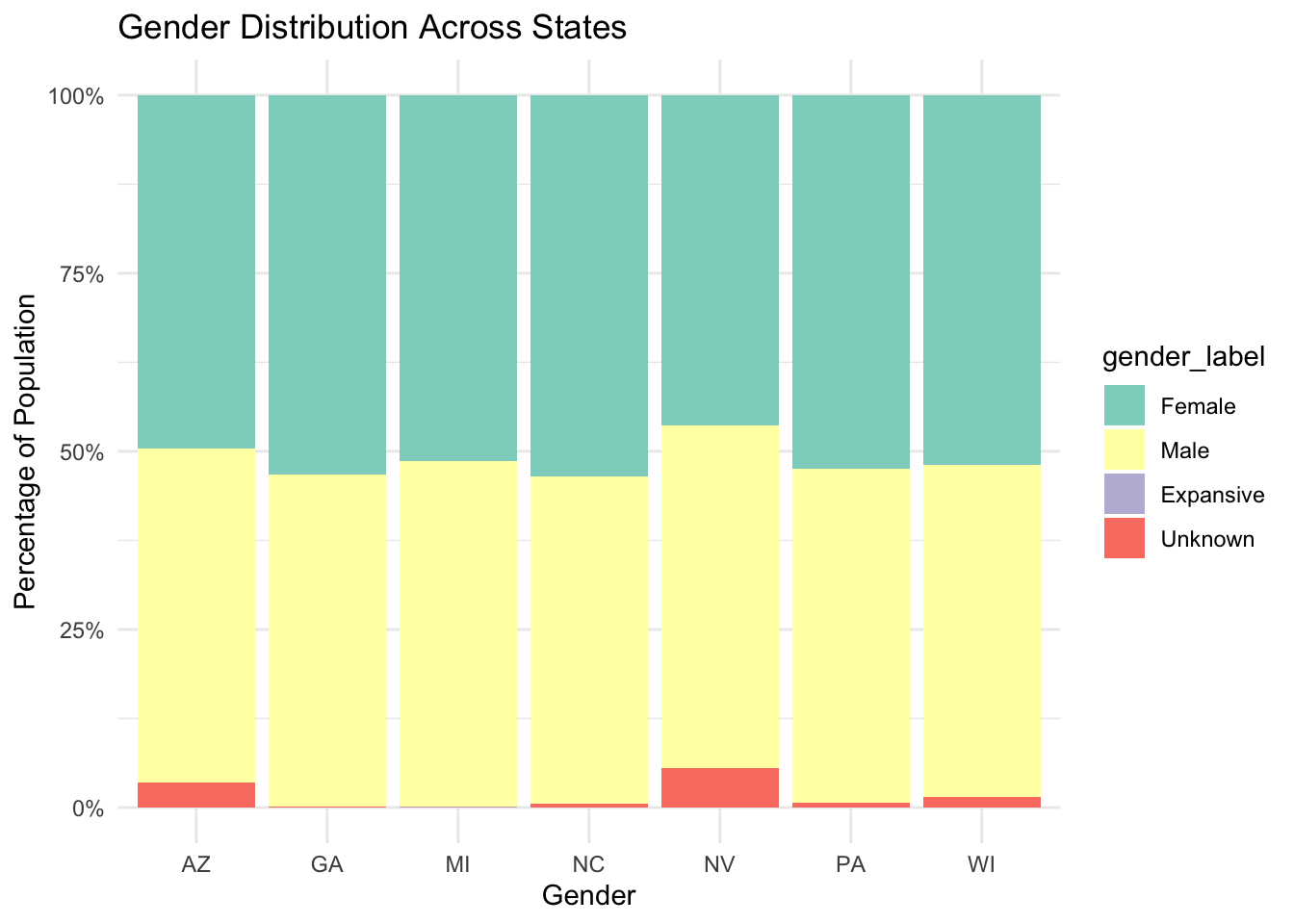

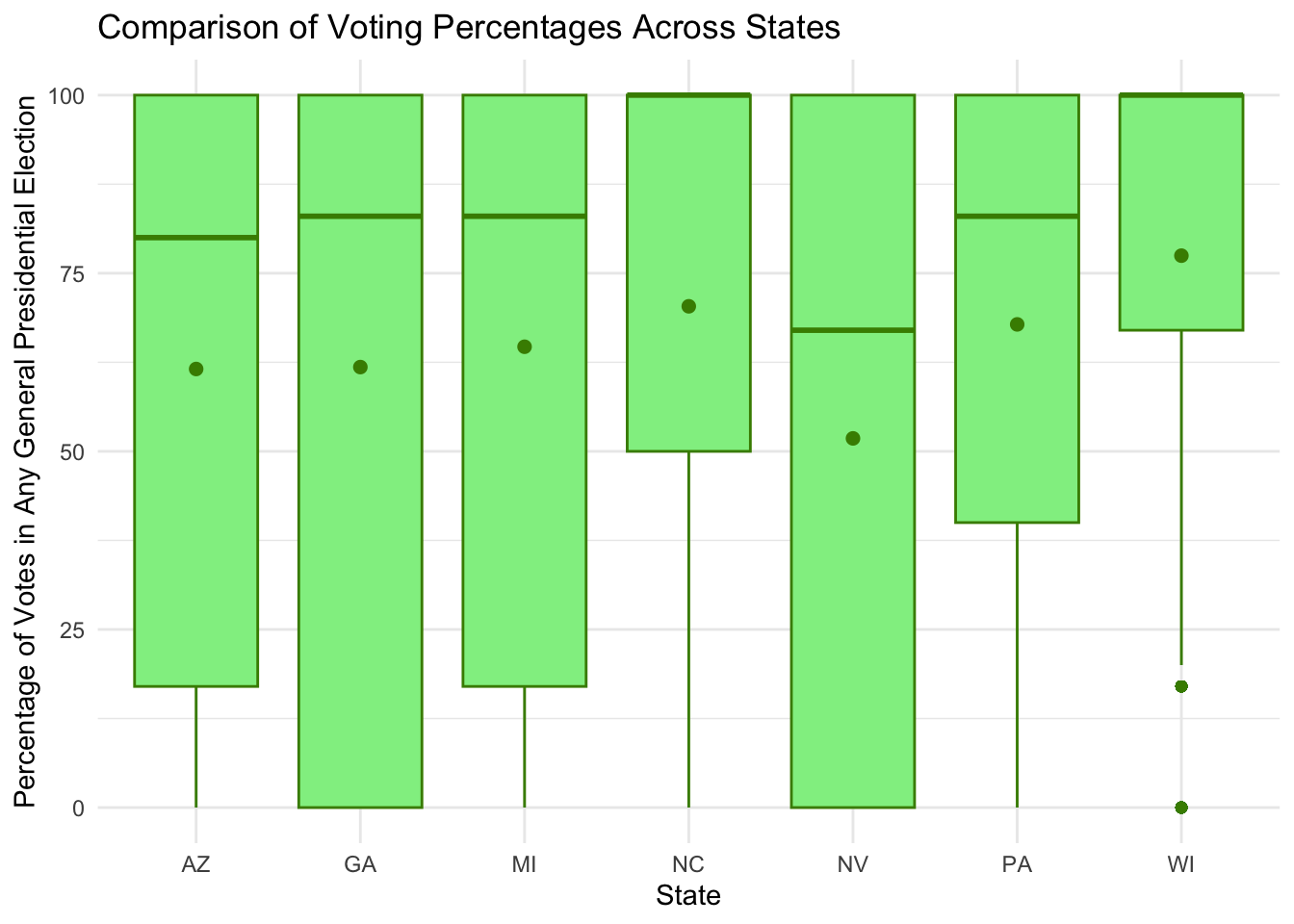

Comparison of demographic data in all battleground states

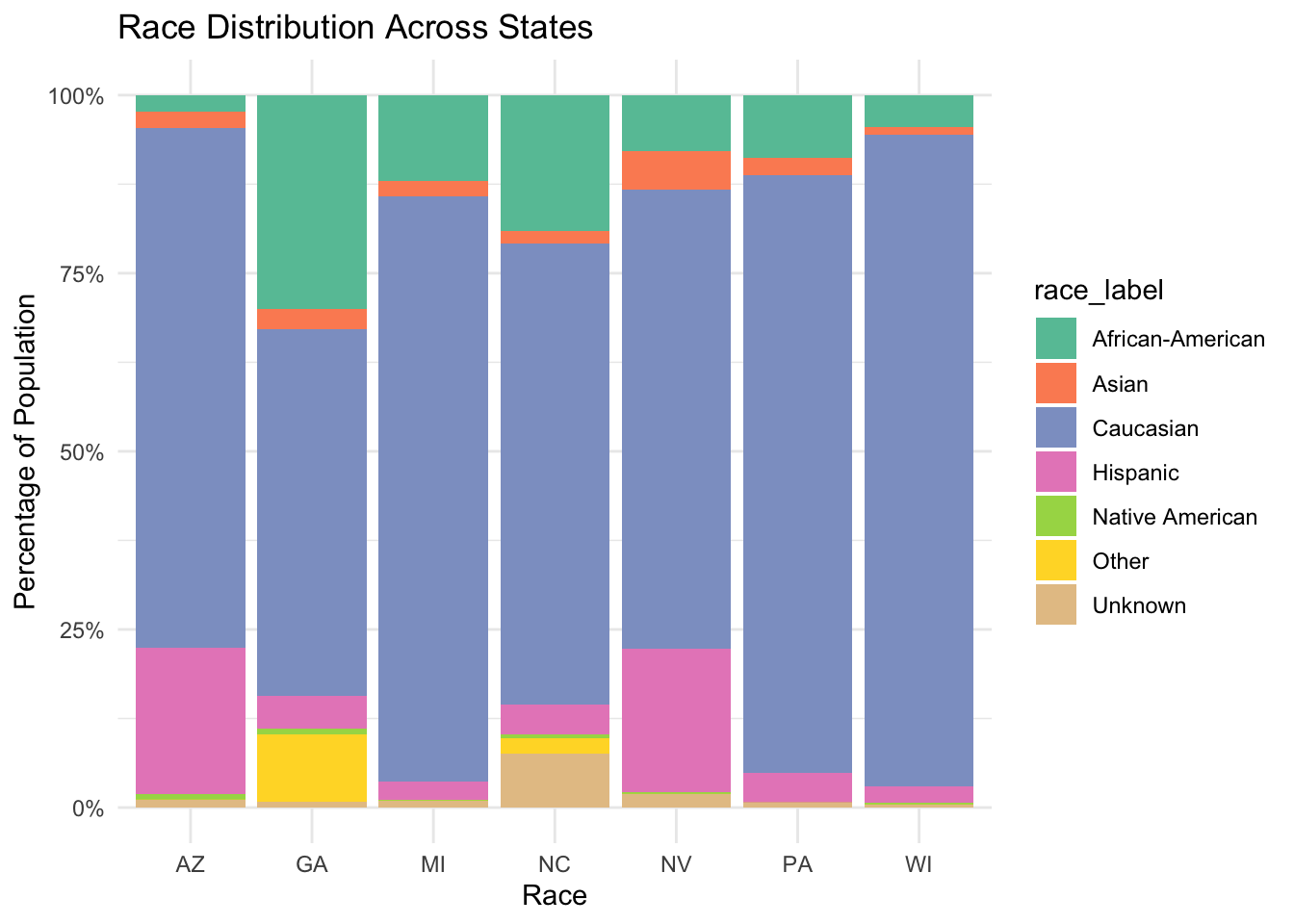

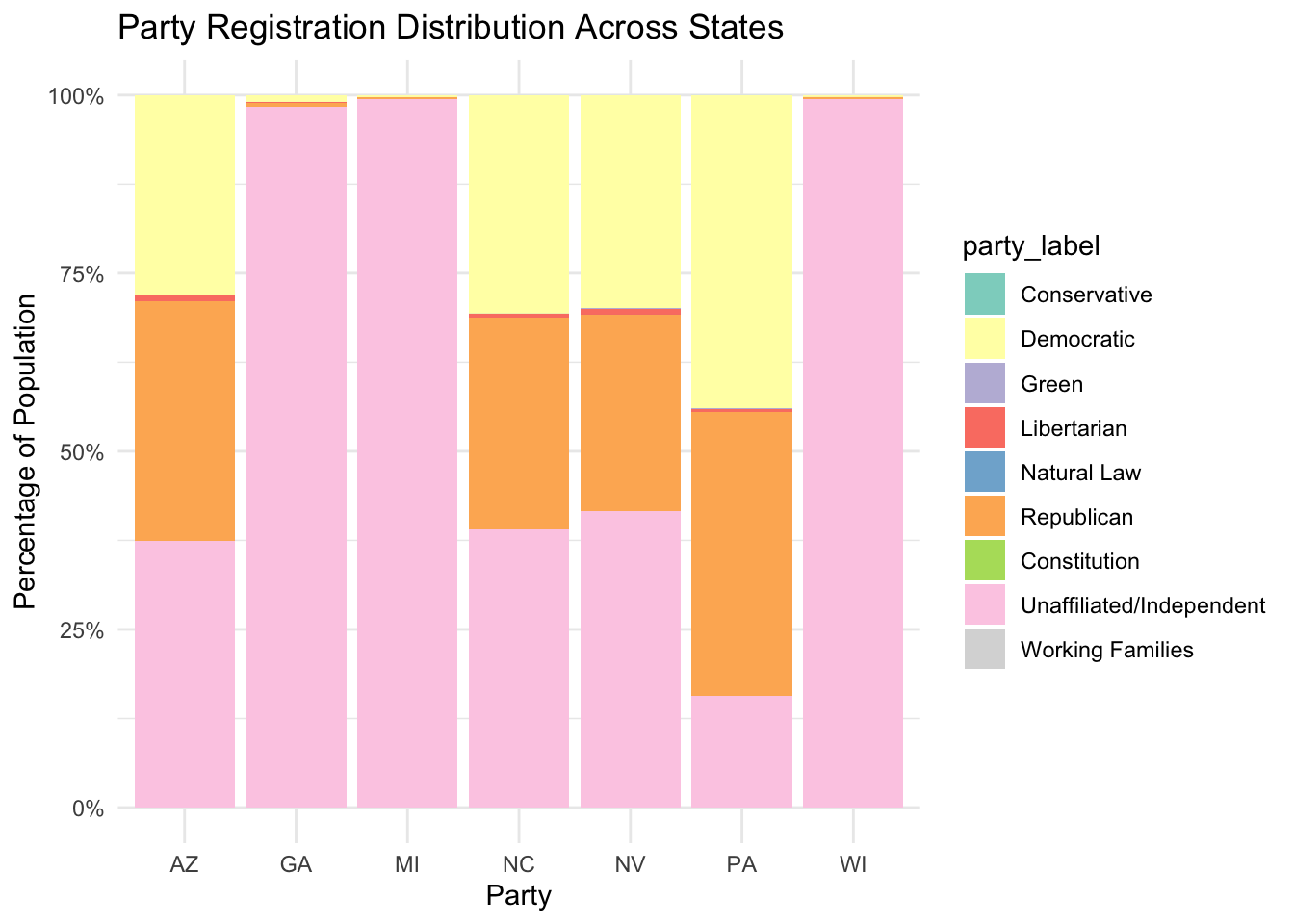

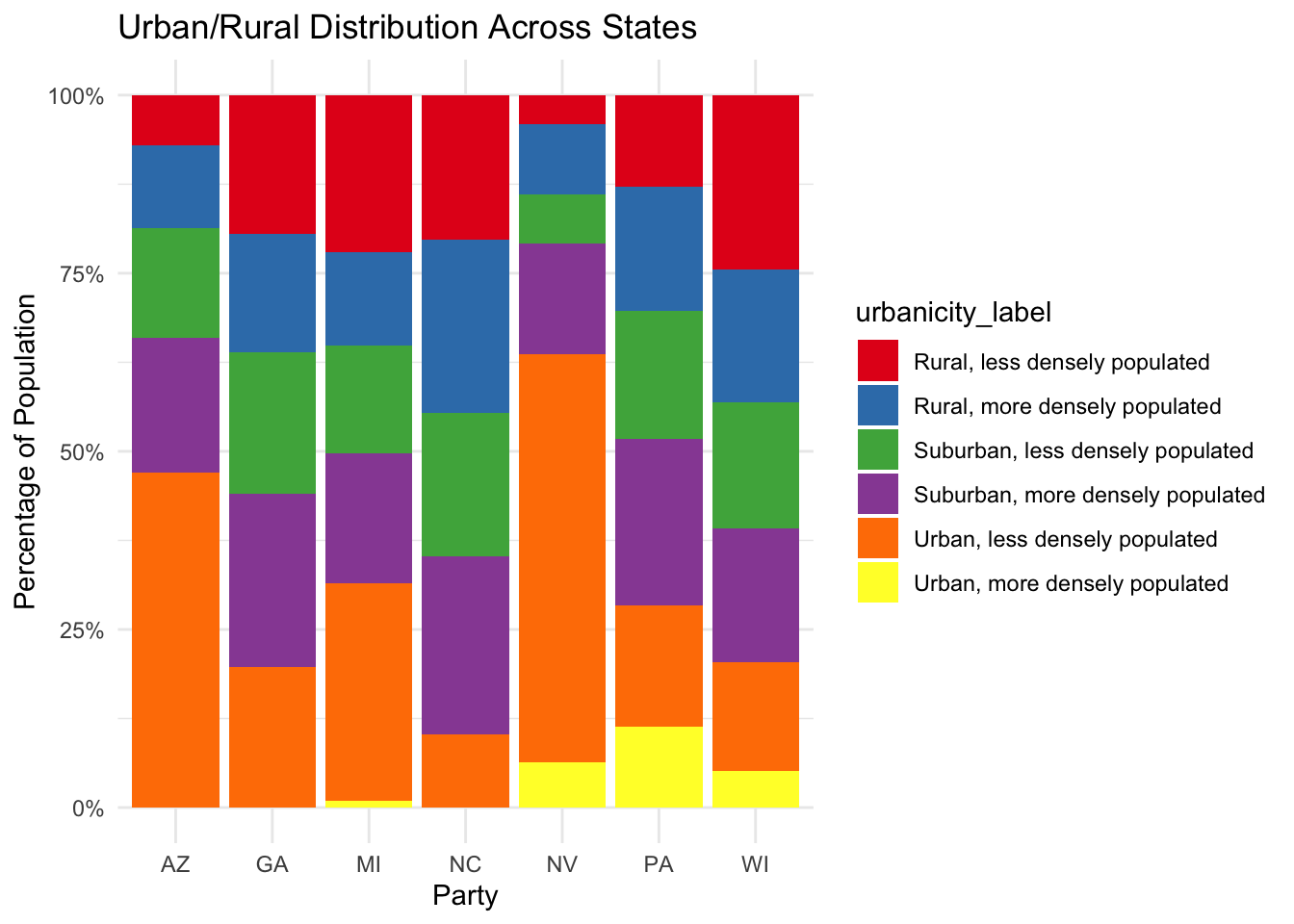

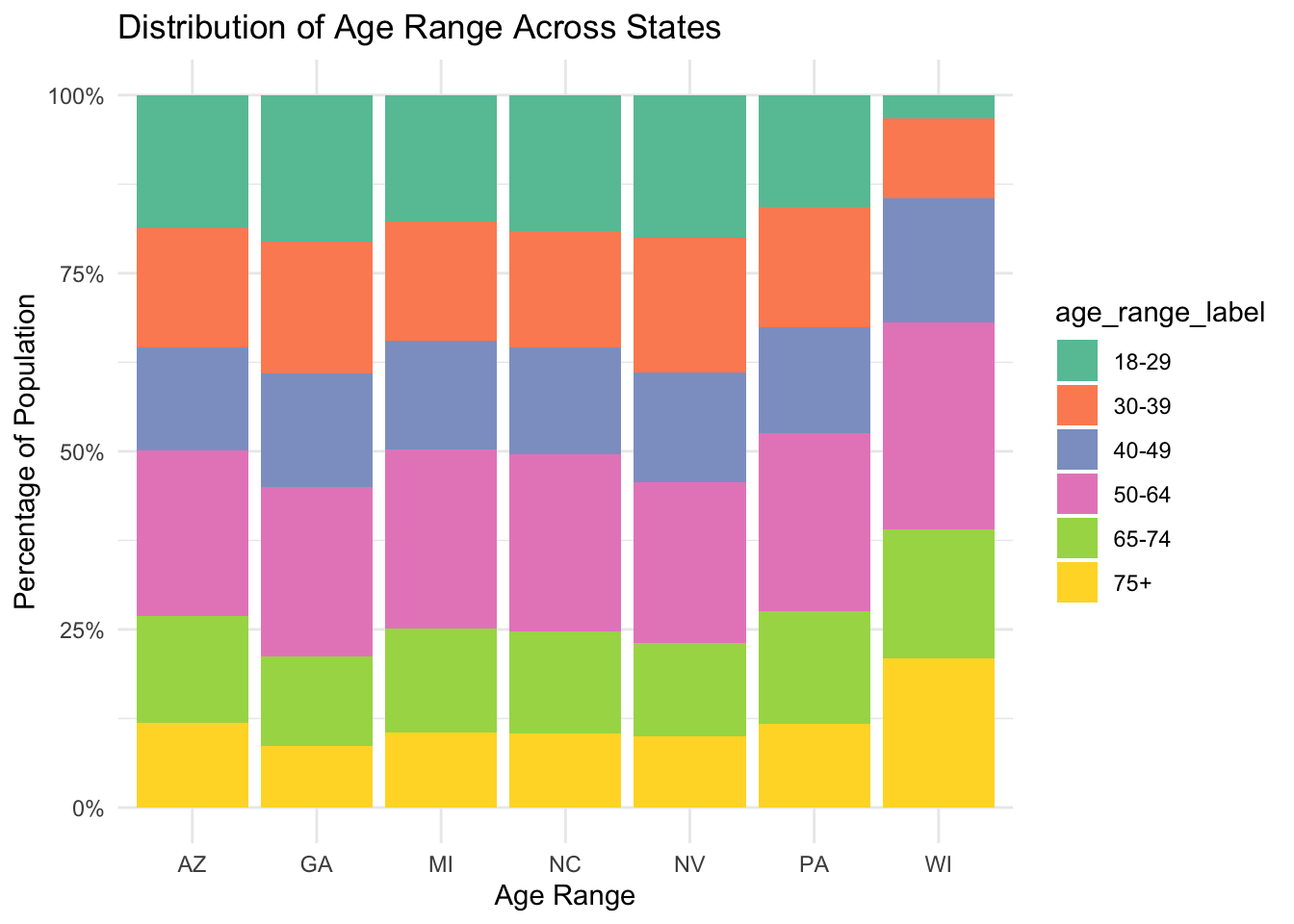

The following plots compares the demographic distribution in all seven battleground states: Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

Code developed with the assistance of ChatGPT.