Election Blog

Week 6: The Air War

The Costly Campaigns

From television commercials in the 20th century to Facebook ads and TikTok videos today, the air war—campaign advertising through mass media—has become a vital element of elections.

According to opensecrets.org, federal spending for the 2020 U.S. election reached an unprecedented 14.4 billion USD, with 5.7 billion USD spent on the presidential race alone. This made U.S. elections the most expensive in the world.

In previous blogs, I explored the predictive power of fundamentals like the economy, incumbency, and demographics in shaping election outcomes. But how do dynamic factors (that can be a result of choices of candidates), such as campaign efforts, influence elections when “voters are predictably partisan” and “the economy strongly shapes election results?”

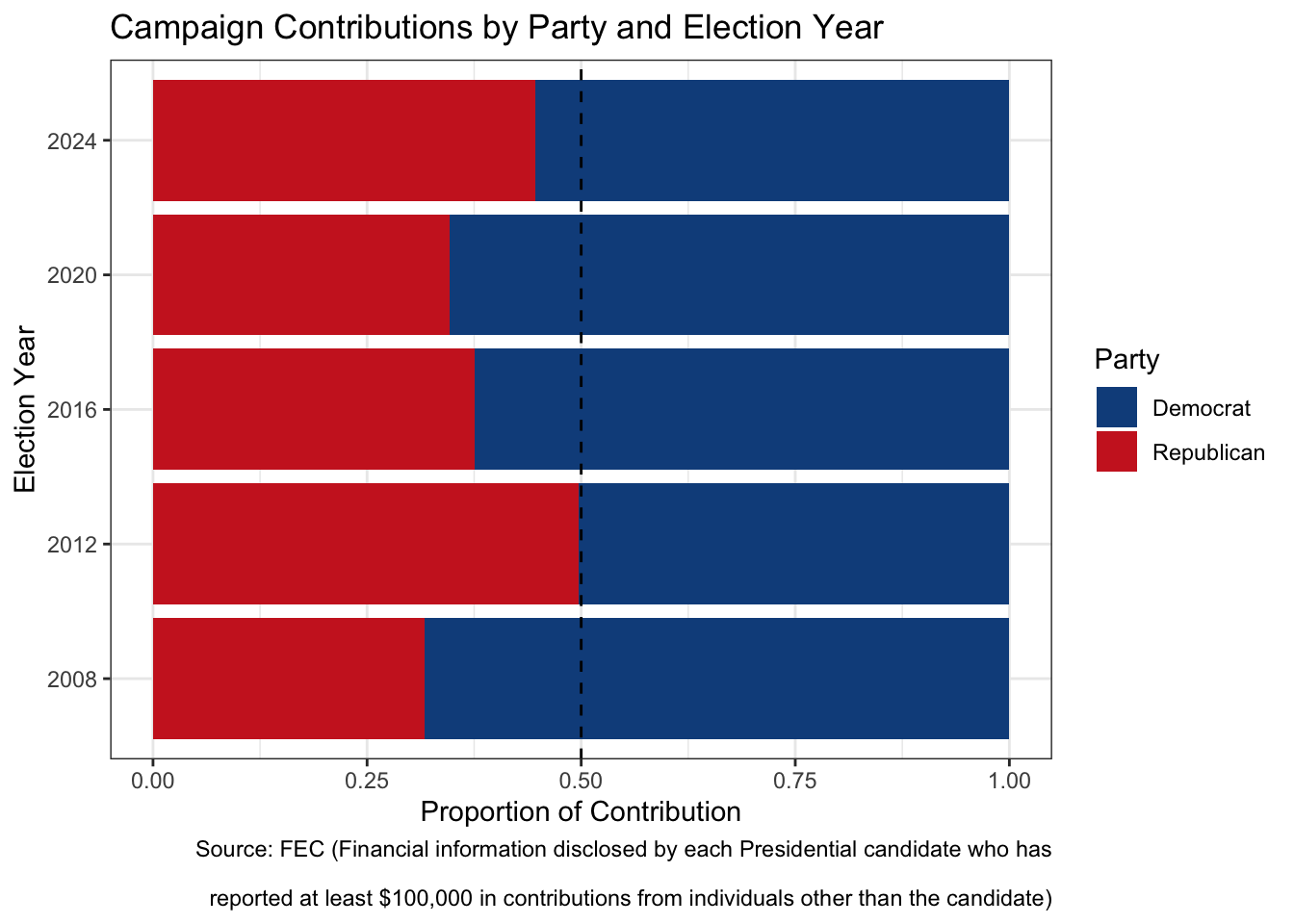

Sides & Vavreck (2013) argue that while campaigns can shift votes through air wars (advertising) and ground games (field organizations), it is difficult for one candidate to gain enough support to change the polls dramatically or eventually win decisively. Think of a presidential election as a tug-of-war: if the polls remain steady, it doesn’t mean a campaign is weak, but rather that both sides are running effective campaigns. In the 2012 presidential elections, for instance, Obama and Romney, along with their supporters, spent nearly equal amounts of money, making it unlikely that one side had a significant advantage, as seen in the graph below.

Interestingly, in all recent elections except for the 2012 cycle, the Democratic Party often outspend its opponents. So does Sides and Vavreck’s theory hold when a party, particularly the Democrats, spends more? Let’s explore this by comparing campaign spending to vote share.

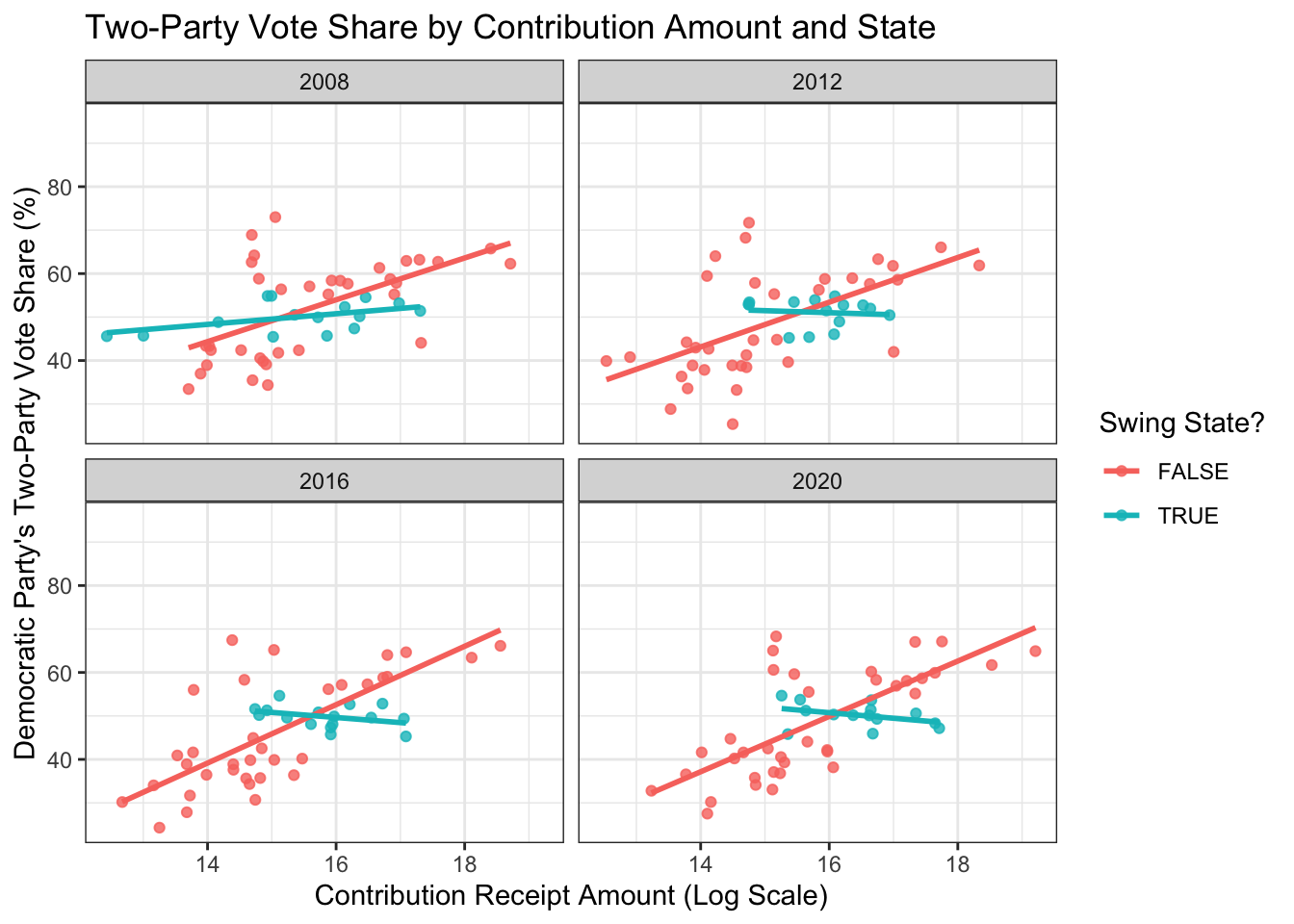

Applying a log transformation to the contribution receipt amount provides a clearer picture. This graph highlights that increased spending by the Democratic Party correlates with a higher vote share, although the impact may not be dramatic, as the increase in vote share is more gradual when contributions are exceptionally large. In fact, the effect is much smaller in swing states, and even reversed in the 2012, 2016, and 2020 election cycles, showing that larger contribution amount does not necessarily translate to higher vote share, and other factors might play a larger role in influencing voters’ decisions.

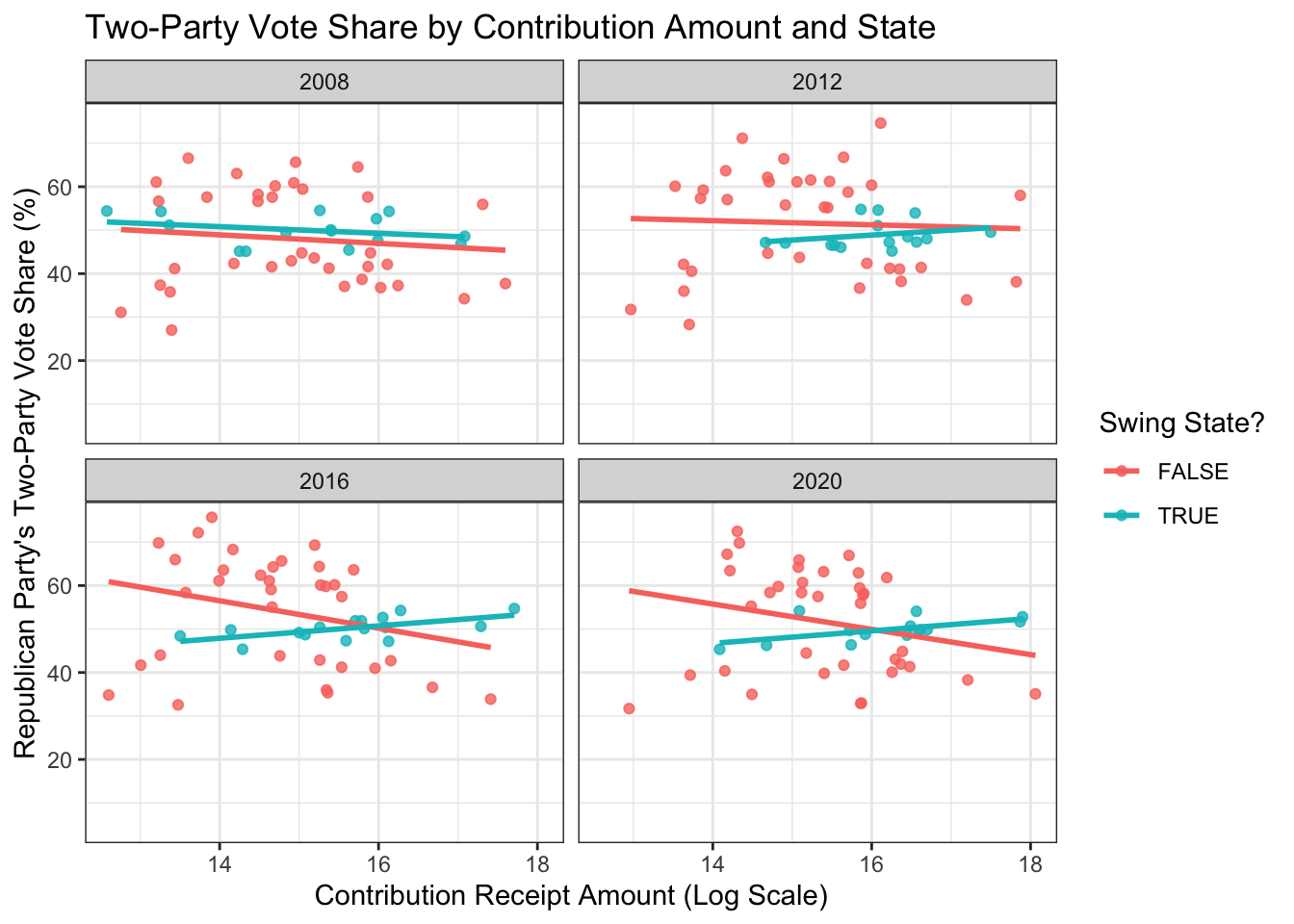

The impact of campaign contributions on the Republican Party’s vote share is even more ambiguous, as illustrated in the graph below. In non-swing states, there appears to be a negative correlation between increased Republican contributions and vote share, particularly in the 2008, 2016, and 2020 elections. However, in swing states, there is little to no relationship between increased contributions and vote share, suggesting that the relationship between the Republican Party’s spending and vote share varies inconsistently across election cycles and state competitiveness. This aligns with findings that advertisements have little mobilization effect but do have a persuasive effect (Huber & Arceneaux, 2007), and that the persuasive effects of advertisements are short-lived (Gerber et al., 2011). Therefore, I will not factor in the “air war” (advertising) in my final election prediction.

What Does the Air War Entail?

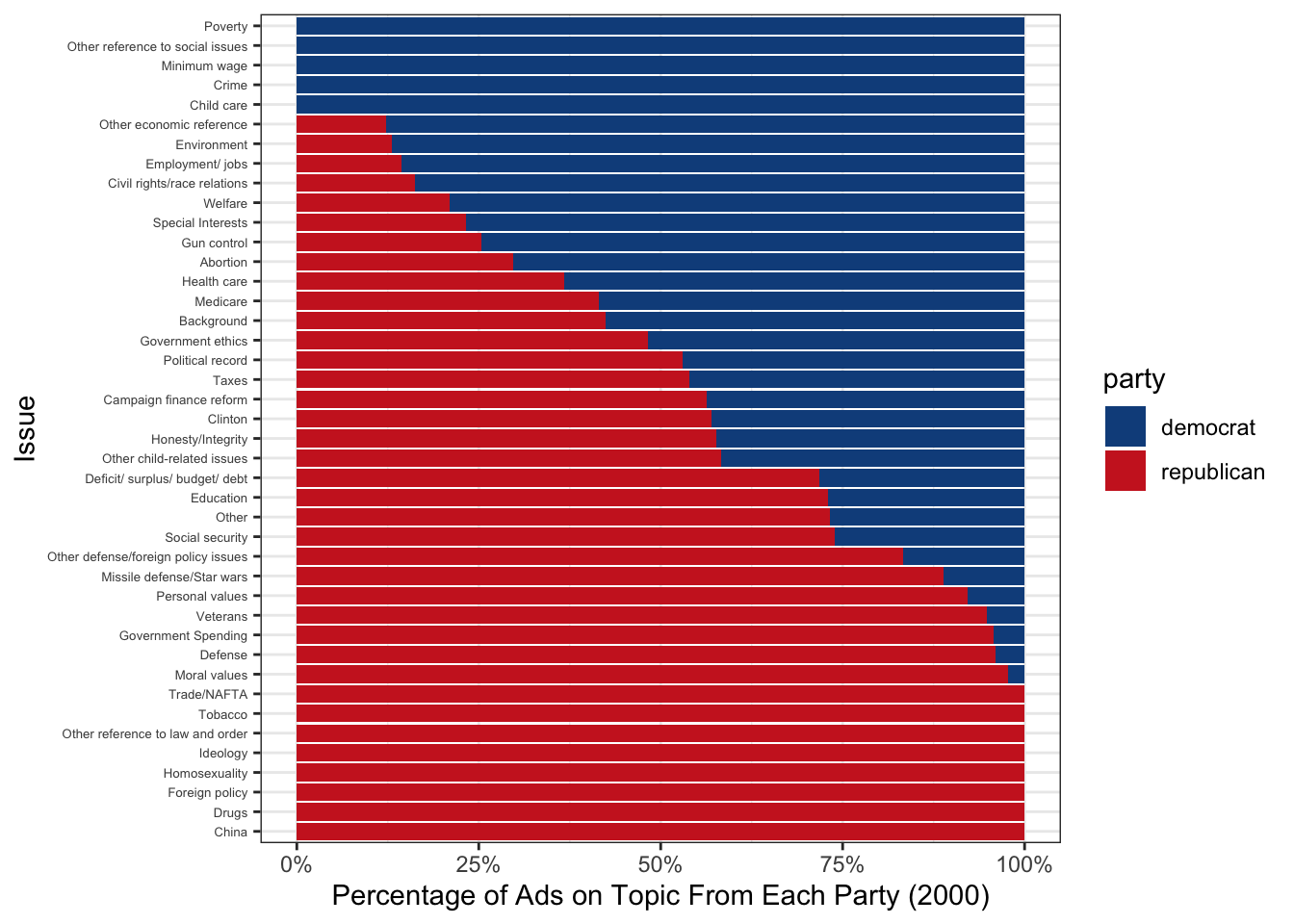

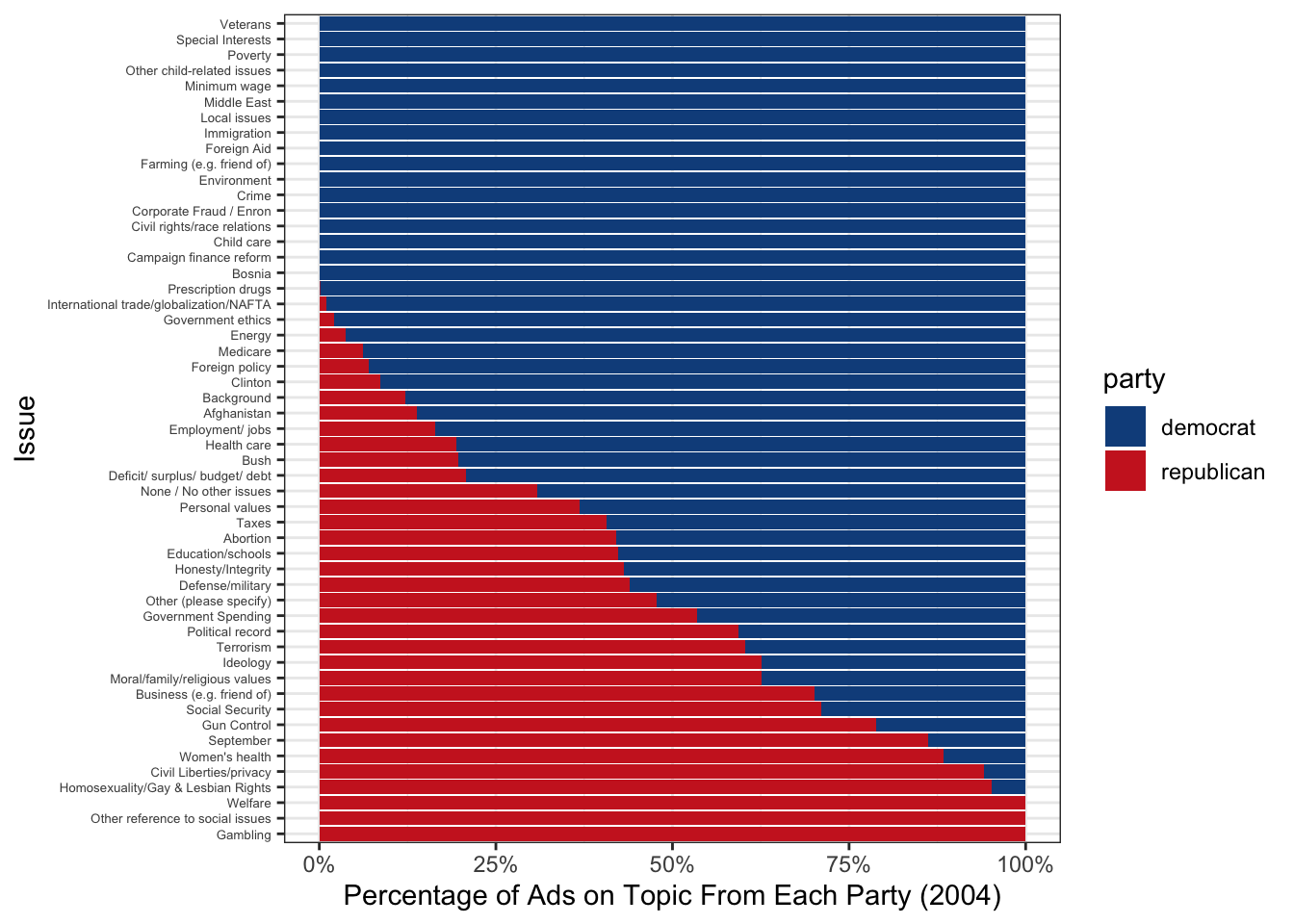

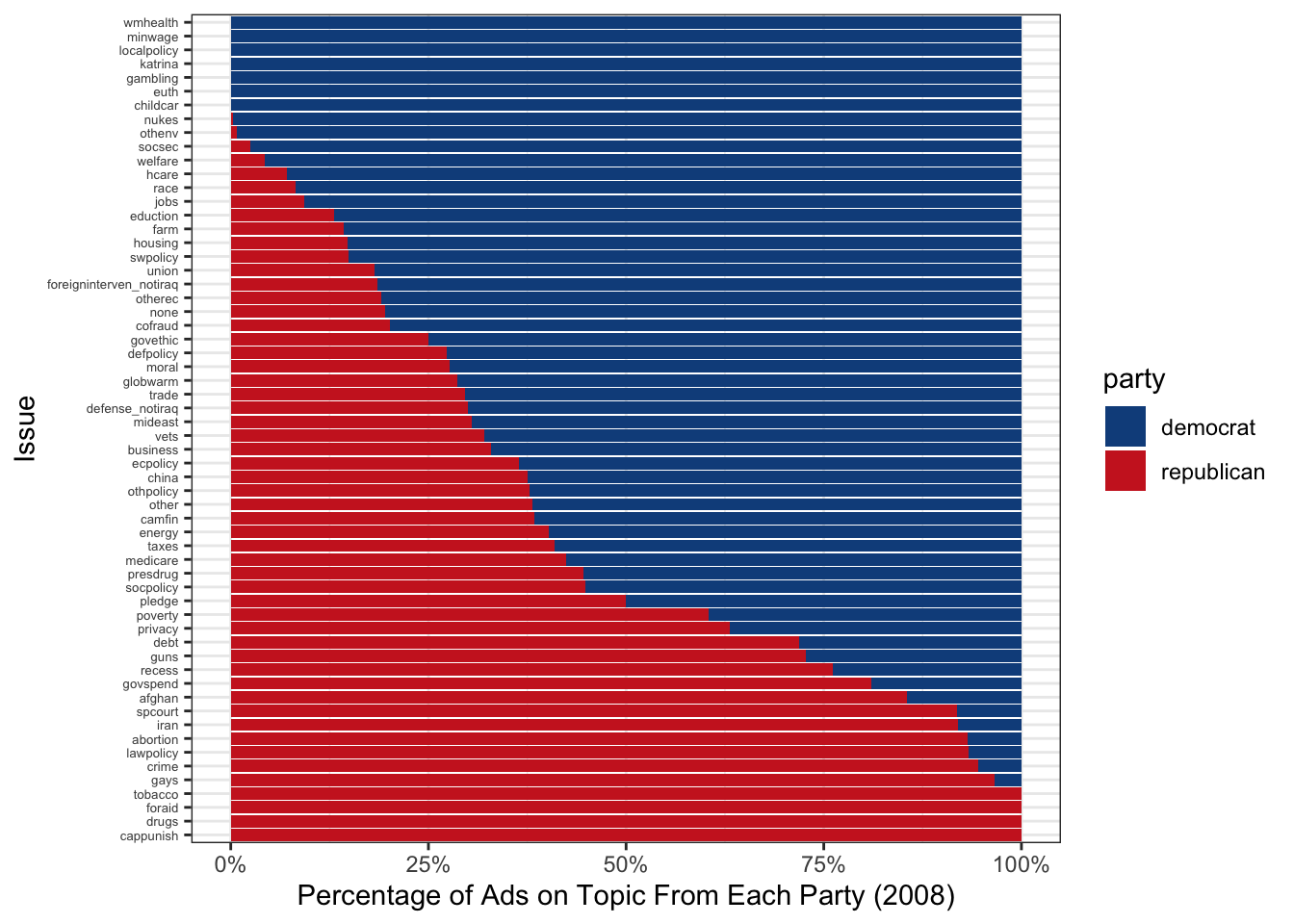

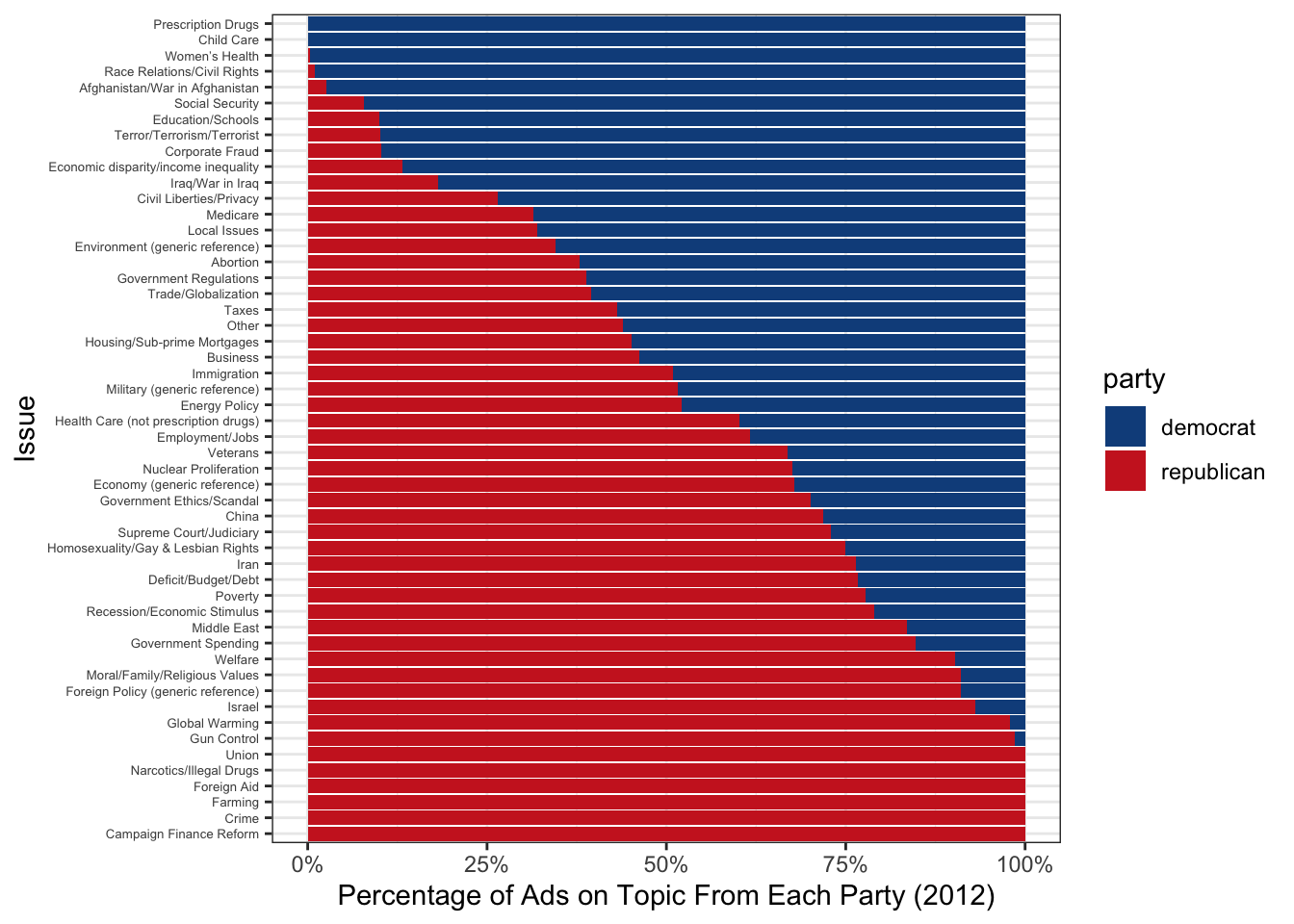

Data from the Wesleyan Media Project offers insights into campaign messaging and values of both parties. Over the years, the Democratic Party consistently emphasized social welfare and healthcare issues, with an increasing focus on economic matters during times of financial crises (2008 and 2012). The Republican Party consistently highlighted national security, defense, and economic issues like taxes and government spending, adjusting their messaging based on the economic or political environment, such as post-9/11 security concerns in 2004.

Code developed with the assistance of ChatGPT.