Election Blog

Week 7: The Ground Game

In the 2008 presidential election, the Obama campaign’s “Get Out the Vote” phone drive on the eve of Election Day introduced a new level of individual targeting strategy in political campaigns. Voters were asked specific questions like “Where will you be just before you vote?” and “What route will you take to get there?” Campaigns focused on being physically present and engaging with individual voters to (1) mobilize voters to turnout and (2) persuade voters to vote for their candidate. This personalized “ground game” method complements the “air war” of mass media outreach. Beyond phone calls and emails, ground game tactics include campaign rallies, community events, and door knocking to foster direct voter engagement.

Conveniently, this weekend, I had a first-hand experience in door-to-door canvassing in suburban areas of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. As an international student, it is exciting to witness the ground game in arguably one of the most important elections in the world!

Ground Game as a Means for Persuasion

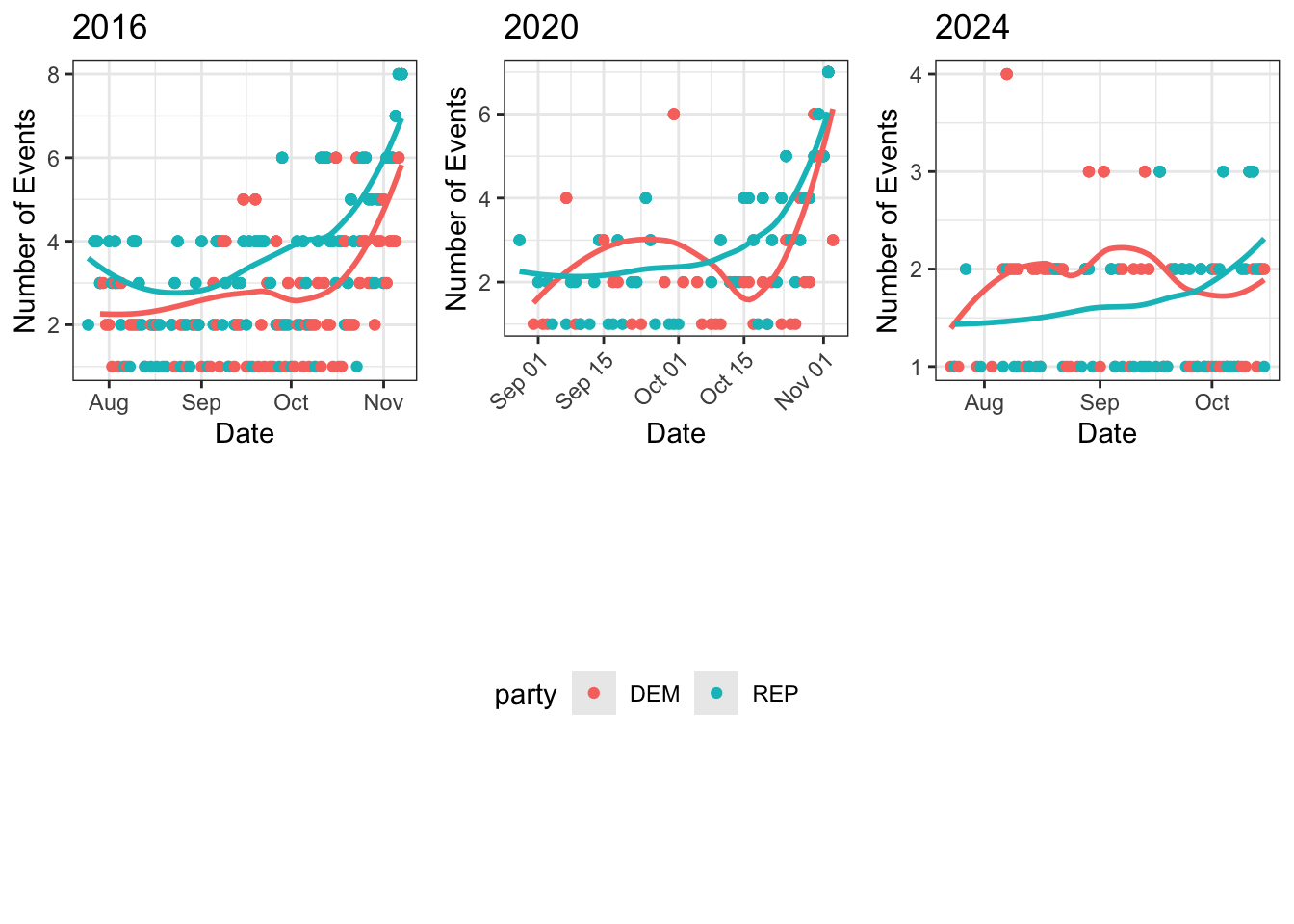

Kalla & Broockman (2018) found that persuasive effects are not durable because campaign contacts attempting to persuade voters often lose impact over time. This suggests that campaigns should focus persuasive efforts right before the election when the message is still fresh in voter’s minds. In reality, campaigns do exactly that, supported by the graphs below that visualize the increasing number of campaign events leading up to the election day.

The regression model shows that on average, the number of events by the Democratic Party is associated with only 0.057 increase in vote share whereas Republican events show a surprising -0.057 decrease in vote share, but both effects being statistically insignificant.

| Predictor | Estimate | Std. Error | t value | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 49.6054504 | 1.8225404 | 27.2177513 | 0.0000000 |

| n_ev_D | 0.0568470 | 0.1671652 | 0.3400650 | 0.7352611 |

| ev_diff_D_R | 0.1611186 | 0.3367149 | 0.4785016 | 0.6344214 |

| Predictor | Estimate | Std. Error | t value | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 50.3941454 | 1.8226083 | 27.6494659 | 0.0000000 |

| n_ev_R | -0.0568322 | 0.1671714 | -0.3399634 | 0.7353371 |

| ev_diff_R_D | 0.2179816 | 0.3904910 | 0.5582245 | 0.5792330 |

Overall, number of campaign events do not seem to directly influences the two-party popular vote share of either side.

Ground Game as a Means for Mobilization

While persuasion may have limited durability, mobilization efforts have strong cumulative effects in ensuring voter turnout (Enos & Fowler, 2016). In places where campaigns are active through calls, emails, and ground efforts like door-knocking, voter turnout can increase by up to 7 percentage points. Campaigns should therefore strategically build field offices in areas where they want to maximize voter turnout among likely supporters.

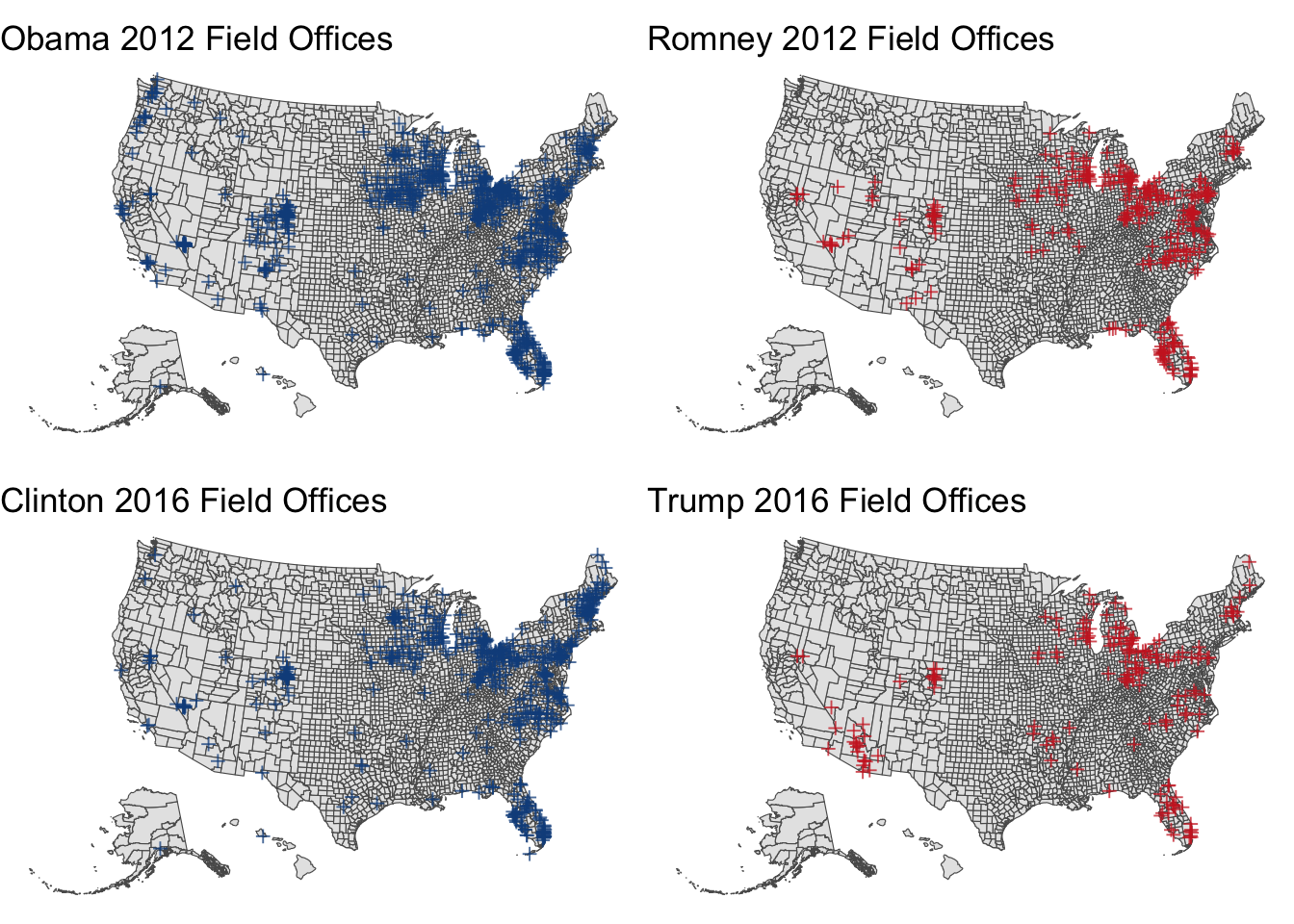

The following maps show that both parties had significant field offices in key battlegrounds like Ohio, Florida, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and North Carolina in both 2012 and 2016, reflecting the critical importance of these states in determining electoral outcomes. The Democrats’ strategy, especially in 2012, involved a broader national reach with field offices even in states like Colorado and Nevada, whereas Republicans, particularly in 2016, focused more narrowly on the Midwest such as Arizona and placed fewer offices in the West in comparison.

When there is an increase in the number of field offices, voter turnout significantly increases by 0.01 percentage points, on average, holding other variables constant. Battleground state have a significant 0.026 percentage point increase in turnout, highlighting that competitive states have higher voter engagement. Although field office increases and battleground status independently increase turnout, there is no clear evidence that their combination has an effect on voter turnout beyond their individual contributions.

| Predictor | Estimate | Std. Error | t value | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.0269512 | 0.0026787 | 10.0611744 | 0.0000000 |

| dummy_fo_change0 | 0.0019318 | 0.0016781 | 1.1511987 | 0.2496951 |

| dummy_fo_change1 | 0.0101933 | 0.0026376 | 3.8646975 | 0.0001124 |

| battleTRUE | 0.0263065 | 0.0037904 | 6.9403672 | 0.0000000 |

| dummy_fo_change0:battleTRUE | -0.0017180 | 0.0036334 | -0.4728408 | 0.6363435 |

| dummy_fo_change1:battleTRUE | -0.0065803 | 0.0043013 | -1.5298427 | 0.1261070 |

An increase in the number of Democratic Party’s field offices increases their vote percentage significantly by 0.023 percentage points, while battleground states have a significant 0.031 percentage point increase in vote percentage for the Democratic Party. Again, while both factors independently boost vote share, they do not amplify each other’s effects.

| Predictor | Estimate | Std. Error | t value | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.0209137 | 0.0040371 | 5.1803260 | 0.0000002 |

| dummy_fo_change0 | 0.0010424 | 0.0025291 | 0.4121772 | 0.6802239 |

| dummy_fo_change1 | 0.0228992 | 0.0039751 | 5.7606770 | 0.0000000 |

| battleTRUE | 0.0311635 | 0.0057125 | 5.4553313 | 0.0000001 |

| dummy_fo_change0:battleTRUE | 0.0144252 | 0.0054760 | 2.6342689 | 0.0084529 |

| dummy_fo_change1:battleTRUE | 0.0084355 | 0.0064825 | 1.3012631 | 0.1932170 |

Although changes in the number of field offices are correlated with shifts in vote percentages, this correlation could be influenced by a confounding factor: political parties are simply more motivated to establish additional field offices in competitive states. These states are naturally more likely to experience fluctuations in vote percentages due to their competitive nature, rather than the presence of more field offices directly causing these changes. As a result, I’ve decided not to include the dynamic ground game factor in my final prediction model.

Stay tuned for my prediction!